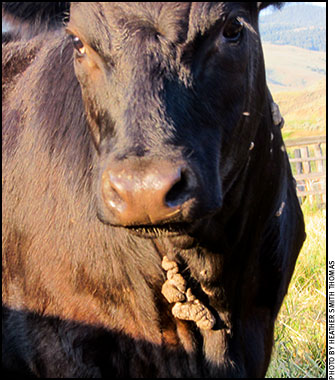

Warts Are Most Common in Young Cattle

Warts often appear in yearlings and are contagious, often spreading to multiple animals in the group.

Warts are caused by bovine papillomaviruses. Cattle have more problems with papillomaviruses than other domestic animals. J. Dustin Loy, assistant professor of veterinary diagnostic microbiology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, says, “Papillomaviruses are species-specific, except that some of the cattle viruses may induce warts or wart-like lesions or sarcoids in horses.”

In a typical papilloma that appears on the skin, immune response in the abraded skin is important to fight the virus. This is why some people use a wart vaccine to reduce incidence of warts.

“There are at least 12 types cattle can get. Some appear in different locations on the animal, and, depending on the type of virus, they may not all look the same,” he says.

They can enter the skin through any injury or scrape. These viruses can also be transmitted by fomites — objects like grooming tools, halters, an ear-tagging tool used on more than one animal, etc., he explains. If you use the tool on a calf that has a papillomavirus and then on a naïve calf, the virus can be passed to the naïve animal. If cattle rub on fences or on each other, the virus can spread readily.

Warts appear, grow larger and more numerous, and after a few months become smaller, dry up and fall off after the animal mounts an immune response. Most types of warts are simply unsightly, but some cause problems — such as penile warts on young bulls. The bull may have trouble breeding, and the warts can cause scarring on the penis.

“Certain types can cause alimentary lesions or internal tumors if ingested. The papilloma viruses can remain viable in the environment longer than many viruses. They have a nonenveloped capsid and a double-stranded DNA genome, making them stable. This is how they can survive for long periods on a halter, ear tagger or grooming comb. They are less sensitive to UV rays in sunlight, or drying, and are hardier than an enveloped virus. BVD virus, for instance, doesn’t survive long in the environment and usually requires direct contact to spread from animal to animal,” he explains.

In a typical papilloma that appears on the skin, immune response in the abraded skin is important to fight the virus. This is why some people use a wart vaccine to reduce incidence of warts. The vaccine must contain the right antigens, because there are 12 different types, Loy says. Some producers have an autogenous vaccine made from samples of wart tissue collected from several of their animals.

“The vaccine will prevent infection through antibodies. To get warts to regress, if the animal already has warts, it takes a cell-mediated immune response. This type of immunity takes much longer to develop. It generally takes three or four months for the animal to get rid of warts because the body has to develop recognition of the virus and fight it,” Loy explains. Most people don’t vaccinate because warts will eventually disappear on their own.

A healthy young animal that gets warts because it has not been exposed to the virus before will mount an immune response and get rid of the warts within a few months.

“The first thing you notice is that the animal stops getting new warts because the immune system has mounted a good antibody response. The old warts remain longer because it takes longer for cell-mediated immunity to occur,” says Loy.

Older animals generally don’t get warts because they’ve already encountered the viruses and have some immunity — unless they become exposed to a different strain.

“If they become immune-suppressed, or have skin trauma, warts may locally recur because the virus may still be there. Generally, however, once they’ve recovered and gotten over the warts, they don’t get them again,” he says.

A common treatment, he says, is to debulk the large warts and crush some. This helps the animal get rid of them more quickly because it increases exposure of the viral antigens to the bloodstream, where the immune system can then recognize them. Warts are typically superficial — on the skin — and there’s not a lot of contact with the blood and lymph system. The antigen has to get to the lymph nodes and have those viral proteins exposed to the immune system.

Editor’s Note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho.