cutline

Disease Factors that Affect Fertility in Cows

Sexually transmitted reproductive diseases can reduce cow fertility.

Eduardo Cobo, assistant professor for the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Calgary, says two of the main reproductive diseases that reduce pregnancy rates in cows are trichomoniasis (trich) and campylobacteriosis (formerly called vibriosis).

“These diseases are often underdiagnosed. Producers may also think vaccination will prevent problems, but vaccination is not always efficient for protecting cows against trichomoniasis, and hasn’t been fully tested for campylobacteriosis. If a herd has fertility problems and uses natural-service breeding, producers should not ignore the possibility that they have one or both of these diseases,” he says.

Cobo’s former supervisor, Robert BonDurant professor emeritus for the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California–Davis (UC–Davis), found that up to 15% of the beef herds in California had at least one bull infected with trich.

“These diseases are silent and can sneak into a herd,” Cobo explains. They may go undetected until there are too many cows coming up open or calving late.

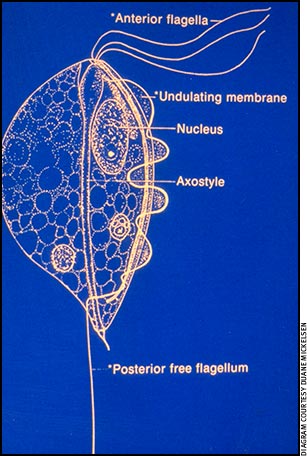

“Trichomonas (the protozoan parasite) can be diagnosed with a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test or a culture, but campylobacter is a tricky organism to culture,” he says. “Usually a veterinarian will not take samples to test for campylobacter for diagnosis because it may be impractical.”

There isn’t a good diagnostic test, so people think the vaccine is working, but this has not been demonstrated, he emphasizes. Trichomoniasis testing has advanced more.

cutline

“Commercial labs can usually grow trichomonas in a culture, and PCR is also used a lot. Many labs can do PCR tests or cultures or both. We have more tools for diagnosing this disease, or for evaluating whether a vaccine works,” says Cobo.

Both diseases kill the embryo or the fetus, mostly in the first three months. The cow is bred and becomes pregnant, but the pregnancy doesn’t last long.

“It’s more like an early embryo mortality than an abortion; you don’t see the fetus. This is different than most of the other reproductive diseases like brucellosis, leptospirosis, IBR (infectious bovine rhinotracheitis) or BVD (bovine viral diarrhea). When those diseases kill the fetus, it might be several months old,” he says.

With trich or vibrio, however, usually the loss is so early and the embryo is so small that it is simply absorbed. You see the cow return to heat and think she didn’t settle from the first breeding. The producer may think it’s an infertile bull. The bull is the one infecting the cow, but the problem is not fertility of the bull, he explains.

The next year you don’t have the pregnancy rate you’d expect. How much the disease might spread depends on age of the bull. A virgin bull is safe to use because he won’t be infected. If you use a virgin bull on heifers (that have never been infected) there is no chance for these reproductive diseases to occur.

“If a bull is very young and breeds an infected cow, he may spread the disease for a while, but there’s a good chance he will get over a trichomoniasis infection himself,” Cobo says. “The prepuce of a young bull doesn’t have as many deep folds where the trichomonas can hide. Trichomoniasis is more chronic in older bulls; they may silently carry it into the next year’s breeding season. So one approach is to use young bulls and not keep a bull past four years of age.”

Some cows can carry the infection from one year to another, and infect a bull that breeds them the next year. Even though the bull is the main carrier, cows can sometimes act as carriers, as well. A study at UC–Davis infected cows and followed them, and found that some cows still had the infection more than 300 days later.

Editor’s Note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho.