Grazing Can Reduce Wildfires

If livestock can be grazed in balance with their feed source, wildfires are kept to a minimum and are not as devastating.

Many people today think fire is “natural,” but devastating fires are not. Grazing is healthier for the landscape.

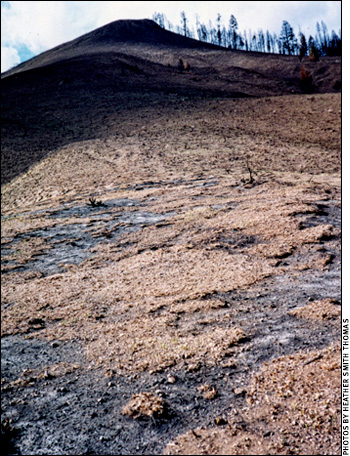

A fire can burn into the top layers of soil and destroy all plant life — roots, seeds, etc.

“Fire can oxidize a lot of material and waste it, whereas grazing recycles it better,” says Fred Provenza, professor emeritus in the Department of Wildland Resources at Utah State University.

Native Americans burned the prairies, and lightning set some fires, but those areas were also being grazed — with large herds of bison, elk and antelope. There wasn’t a lot of fuel load to carry a major fire. A fire episode was usually a flash-through that didn’t damage so much.

Fire is the biggest problem in areas that are not grazed enough, such as western rangelands that have had livestock numbers reduced by land management agencies. If there is too much fuel load, it is a hotter fire that destroys plant roots and seed bank, and it damages top layers of soil. Then there will be nothing but opportunistic invasive weeds coming back in because the perennial grasses, forbs and shrubs are gone.

“This is one reason we now have so much cheatgrass across the western U.S., and a sagebrush fire/cheatgrass fire cycle exacerbates the problem,” says Provenza.

Today some of the most devastating fires occur in areas that haven’t had adequate grazing — with too much old, tall dry grass and extensive fuel loads, according to Richard Teague, Texas A&M AgriLife Research rangeland ecology and management scientist at Vernon, Texas. When an area is periodically grazed, heavy fuel loads are reduced and a fire that goes through now and then is not such a catastrophic or devastating event.

Today some of the most devastating fires occur in areas that haven’t had adequate grazing — with too much old, tall dry grass and extensive fuel loads, according to Richard Teague, Texas A&M AgriLife Research rangeland ecology and management scientist at Vernon, Texas.

“Fire can be very damaging, especially in a low rainfall area. In my area of Texas, we get about 22 inches of precipitation annually on average. I asked the question: When a region burns, how long does it take for essential ecosystem functions like water infiltration, nutrient status and carbon status to recover after a fire? The answer: It takes three average or better-than-average rainfall years for that to happen. But how many years does it take to get three average rainfall years? It takes about eight years.”

Thus fire can have a negative impact on the ecosystem for a long time, especially if it burned hot enough to destroy plants, root systems, seed bank, top layers of soil and its microbes.

Good grazing management is required after burning to speed up the recovery process, says Teague.

“A fire removes vegetation that protects soil from exposure to sun, raindrop action and overland water flow (which increases soil erosion), and damages soil biological function until plant cover is restored. Good grazing management is required after burning to speed up the recovery process,” says Teague.

We want less bare ground and higher soil organic matter, thus fire is counterproductive. In one of his studies, he looked at the amount of bare ground in various range areas, because this is a well-documented way to assess erosion hazard. Erosion hazard increases if there is insufficient plant cover to dissipate the energy of raindrops before they strike the soil.

Previous research on rangelands around the world indicates that bare ground has considerably lower infiltration and higher runoff and erosion than ground covered by perennial grasses. After a hot fire, perennial grasses are often destroyed and the first things that come in are annual weeds, which have less ability to minimize erosion. When drought conditions precede and follow burning, there can be an increase in bare ground and an increase in annual forbs and annual grasses at the expense of perennial grasses.

“In many situations, properly managed adaptive multi-paddock grazing can be healthier for an ecosystem than fire — improving the health and function of the soil to improve water infiltration and retention, energy capture and nutrient cycling,” he says.

Editor’s Note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho.