Clostridial Diseases

Several deadly diseases are caused by bacteria called clostridia.

Several deadly diseases, including blackleg, malignant edema, “redwater” and “overeating disease,” are caused by bacteria called clostridia.

These bacteria form a protective waxy covering in their dormant stage (spores) when exposed to heat or drying, and can remain alive almost indefinitely. Some live in soil for many years and infect animals later when ingested with feed or introduced into a wound. Spores can also exist within the body in a latent state without causing disease, then suddenly come to life and multiply when conditions become favorable.

Niehaus says they think blackleg infection often begins with bruising or trauma, creating damaged tissue which starts the anaerobic process. These bacteria can enter via a direct poke or puncture (such as intramuscular injection) but can also spread to the muscle via the blood.

Clostridia can produce deadly toxins if they get into the bloodstream. Toxins of different types of clostridia vary in their effects and how they gain access. They multiply in the absence of oxygen — such as in a deep puncture wound, in bruised tissue with compromised blood supply, or certain conditions within the digestive tract. When they multiply, these bacteria release deadly toxins faster than the body can mount a defense (unless the animal was previously vaccinated), often causing sudden death.

Many of these bacteria exist in the intestine of normal animals (and humans) as part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract flora. They are fairly ubiquitous in the environment and in the soil. They cause disease in certain situations, as when diet or management changes produce an environment more favorable for swift multiplication. Since most of these bacteria are ever-present, the best way to protect cattle is by vaccination.

Andrew Niehaus, clinical associate professor for the College of Veterinary Clinical Sciences at Ohio State University, says the 7- and 8-way vaccines combine protection against most of the clostridial diseases, including blackleg, redwater, malignant edema, black disease, and enterotoxemia (gut infection caused by Clostridium perfringens types C and D).

“The toxins produced by these bacteria are very potent. Often the only clinical sign we observe is acute death,” he says.

“Clostridium perfringens type C and D are diarrheal diseases and usually only occur in calves. The main disease we are concerned about is blackleg, which is always included in 7- or 8-way vaccine. Most cattle are vaccinated as calves to protect against blackleg, and boostered annually. We don’t worry much about redwater here, but in some regions stockmen must vaccinate annually or even twice a year,” he says.

Liver flukes are a major factor in redwater; they damage the liver and enable clostridial bacteria to proliferate in that tissue.

Today blackleg is rarely seen, perhaps because most cattle are vaccinated. If an animal does get an infection, it must be discovered early to try treatment before the animal dies.

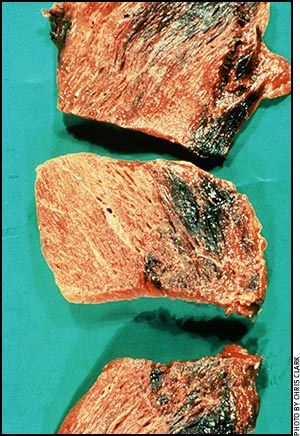

“With blackleg, animals affected are generally fast-growing and heavy muscled — some of the best calves. They’ve been growing well, then suddenly die from clostridial infection. Often there is swelling over heavily muscled areas, and when you touch them it feels like little air bubbles under the skin. This crackly, air-bubbly feeling is called crepitus,” he says.

“Clostridia are gas-producers when multiplying. Gas produced by blackleg accumulates under the skin. All clostridial organisms are anaerobes, thriving in environments devoid of oxygen. They cause muscle damage and necrosis, and the necrotic material provides more habitat for them. It’s a self-perpetuating vicious cycle,” he explains.

Niehaus says they think blackleg infection often begins with bruising or trauma, creating damaged tissue which starts the anaerobic process. These bacteria can enter via a direct poke or puncture (such as intramuscular injection) but can also spread to the muscle via the blood. The animal can ingest blackleg spores from the environment, and they go from the GI tract into the bloodstream and into muscle. The bacteria in spore form may not cause any problems until the muscle is damaged, creating a perfect environment for them to multiply.

Treatment, if the animal is found before death, involves antibiotics and poking holes in the skin to get rid of gas build-up and allow oxygen into the tissues.

“We also try to remove the necrotic tissue and pus, providing drainage. It can be difficult to get antibiotic into necrotic tissues, however, because they have no blood supply. This is another reason these diseases have very poor prognosis, even with treatment,” says Niehaus.

Editor’s Note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho.