Avoid Winter Dehydration

Cold stress and dehydration can negatively affect cattle health.

It is important to provide adequate water for livestock during cold weather. Body metabolism increases during cold weather. Feed intake increases as cattle need more “fuel” to keep warm. To process the additional feed, the digestive tract needs adequate fluid. A cow’s winter water requirement may not be as high as in the heat of summer, but she must drink enough to handle the demands of increased metabolism to prevent dehydration and impaction. If the cow is lactating, she needs more water regardless of weather.

Charles Stoltenow, professor and assistant director of the North Dakota State University Extension Service, says everyone thinks about the importance of water during summer, but not so much during winter.

“Yet a beef cow requires about 1 gallon of water per 100 pounds of body weight, so a 1,200-pound cow needs about 12 gallons daily, which is about 100 pounds of water. One of the hardest things about managing cattle in winter is providing dependable water sources, since ponds, streams or tanks may freeze up or ice over,” he says.

“We can move our feeding site, but it’s not as easy to move our watering sites. We know from our research that if cattle decrease water intake, they will also decrease dry-matter intake (DMI) so it becomes a double whammy. They drink less, so they eat less; so in order to maintain body temperature or maintain a fetus they have to start drawing on their own energy and protein reserves and lose weight,” he explains.

In some areas ranchers have trained their cattle to use snow as a water source. It can be done, but cattle have to learn how to lick snow, which many will do by mimicking their mothers or other cattle, and some are slow to learn. If cattle must use snow, it can’t be crusted, says Stoltenow. They have to be able to scoop it up with their tongue. If it’s gone through a thaw-freeze cycle and is crusted, cattle have a hard time consuming enough snow to supply the water they need.

If they try to chew crusted snow, they can end up with abrasions in their mouth, making it more painful and difficult to graze. This, too, results in decreased feed intake, as well as decreased water intake. It becomes a vicious cycle, he says.

If cattle become dehydrated with decreased feed and water intake, they can’t get the protein and energy necessary for body condition maintenance and pregnancy.

|

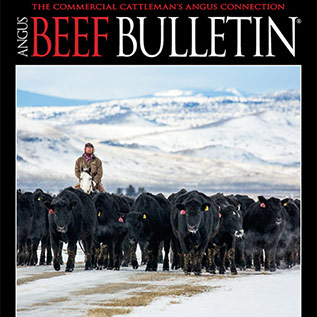

“A beef cow requires about 1 gallon of water per 100 pounds of body weight, so a 1,200-pound cow needs about 12 gallons daily, which is about 100 pounds of water. One of the hardest things about managing cattle in winter is providing dependable water sources, since ponds, streams or tanks may freeze up or ice over,” says Charles Stoltenow. [Photo by Heather Smith Thomas] |

“The fetus, as it develops, is primarily water, muscles and bones. It depends on the dam for all its nutrients (vitamins, energy, proteins, etc.) in order to grow. So if the cow decreases feed intake because she is short on water, she will be short on all nutrients. This shortchanges the fetus for growth and there is inadequate protein for the dam to make enough colostrum and immunoglobulins,” he explains.

We are learning more about fetal programing and the importance of proper nutrients, including water, for the dam during pregnancy — and some things we didn’t think about 20 years ago, he says. Knowing that lack of water can affect the amount a cow eats and that it may have an adverse effect on her unborn calf later, it becomes more imperative to provide adequate feed and water.

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho.