Dealing with Diphtheria in Calves

Learn how to deal with upper respiratory problems in calves.

Upper respiratory problems include diphtheria, an infection that causes inflammation of the vocal folds of the larynx (voice box) at the back of the throat. Swelling from the inflammation can restrict the airways and make breathing difficult.

Steve Hendrick, veterinarian with Coaldale Veterinary Clinic, Coaldale, Alta., Canada, sees quite a few cases of diphtheria in cow-calf operations and feedlots.

“We think trauma opens the way for infection, such as eating abrasive feeds. Trauma can also occur when using a tube feeder on baby calves. If the tube surface is rough instead of smooth (if it got chewed), or the tube is forced abruptly into the throat, it may scrape the larynx,” he says.

The infection is generally caused by pathogens in the environment.

“The main ‘bug’ that causes diphtheria is Fusobacterium necrophorum — the same one that causes foot rot, liver abscesses, and is often found in the gut and upper respiratory tract. Viruses such as IBR (infectious bovine rhinotracheitis) can play a role because they can damage the lining of the respiratory tract and open the way for bacterial infection,” says Hendrick.

Swelling in the larynx narrows the opening and makes more effort for every breath. Air must pass those swollen folds, and they are constantly getting more irritated with each breath by rubbing against each other, he says.

You may hear the calf wheezing. At first you may think its pneumonia because he’s struggling for breath, but if you watch the respiratory effort you can tell the difference. A calf with pneumonia has trouble pushing air out of damaged lungs, whereas a calf with diphtheria makes more effort to draw air in through the narrowed airway.

A calf with diphtheria often drools frothy saliva because he has trouble swallowing.

“He’s so busy trying to breathe that he can’t take time to swallow. Extra salivation can also be due to irritation from sores in the mouth, as well as the throat,” Hendrick says.

Sometimes the infection is in the mouth and not the throat, and that’s not as serious for the calf because he can still breathe.

If swelling in the throat closes the airway, he suffocates. If he’s struggling for breath, staggering from lack of oxygen, you need to slice through the windpipe below the larynx — carefully cutting between the ribs of cartilage surrounding the windpipe with a clean, sharp knife — for the calf to breathe.

Diphtheria is most common in calves, but older animals are sometimes affected. A mature animal has a larger throat and windpipe, however, and may not have as much trouble breathing if this area becomes swollen. The infection may still affect the larynx and can cause enough scar tissue in the vocal folds to affect the voice, says Hendrick. Some cows lose their voice.

“Infection in the larynx is generally responsive to oxytetracycline. We also use penicillin. There are several antibiotics that can be used,” he says.

It may take a long time to overcome this infection, however. Each breath irritates the already swollen voice box and it takes a long time to heal. Blood supply to this area is also limited. That makes getting enough antibiotics to the infection more difficult. Treatment may have to be continued for several weeks.

|

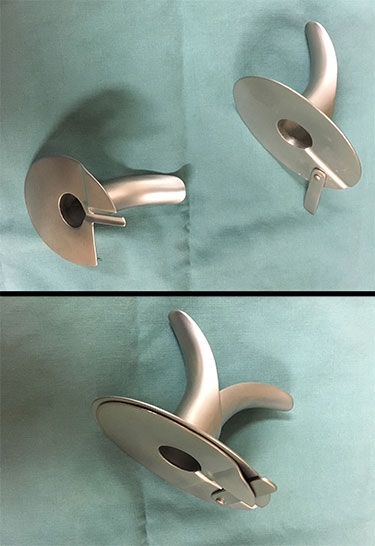

| “A tracheostomy insert can bypass the swollen, irritated larynx and allow the calf to breathe through a hole in his windpipe. Your veterinarian can place it into the calf’s windpipe below the larynx. We have great success with this in baby calves and feedlot calves,” says Steve Hendrick. [Photos by Steve Hendrick] |

Producers need to talk to their veterinarian regarding treatment. Usually if treatment can be started early, it can clear up within a week or two, but don’t stop treatment until it is completely cleared, says Hendrick. If you stop too soon, the calf will relapse. A relapse is much harder to recover from, and you may lose the calf.

“A tracheostomy insert can bypass the swollen, irritated larynx and allow the calf to breathe through a hole in his windpipe. Your veterinarian can place it into the calf’s windpipe below the larynx. We have great success with this in baby calves and feedlot calves,” he says.

“Installing this insert allows him to breathe. And when you take that constant irritation away (air forced past the swollen folds of the larynx), within two or three weeks the calf has healed and we don’t need to keep treating with antibiotics so long,” he explains.

Anti-inflammatory medication is also important to reduce swelling and irritation in the throat. This can ease the calf’s breathing and help irritated tissues start to heal.

“Often we recommend dexamethasone as a single dose at the beginning to help reduce that swelling. We don’t repeat it because prolonged use of steroids tends to hinder the immune system. There are a number of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that can also be used. Discuss this with your veterinarian and treat the calf as soon as you realize he has a problem,” says Hendrick.

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho.