Senses and Sense

To perfect your sport, think like a leader.

Humans developed over millennia to hunt and herd. When it’s time to move animals, instincts send us out with a purpose, but sometimes little thought as to how our aggressive behavior affects what they do.

Stepping into a cattle pen, we naturally act the predator, manipulating where animals go. But good handling practices should turn us into leaders, says Kip Lukasiewicz.

The veterinarian now works through Production Animal Consultation to teach ranchers and cattle feeders across the country how to use their senses — sight, hearing, smell and touch — to understand and guide animals.

Study the behaviors Rather than simply putting animals up front and pushing, a true communicator leads them through any facility or environment.

“I wish people could lose their voice,” Lukasiewicz says, “and learn to directly communicate with their eyes, their position and their posture.”

“Prey animals will give you their ear first,” he adds, “and then their eye.”

That’s when it’s time to make a move.

|

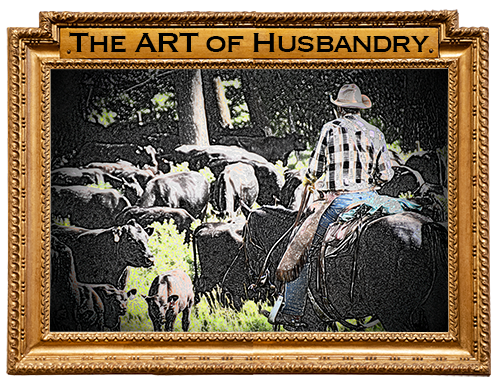

“I wish people could lose their voice,” Lukasiewicz says, “and learn to directly communicate with their eyes, their position and their posture.” A true communicator will lead cattle through any environment. [Photo by Abbie Burnett] |

The speed at which an animal responds is grounded in trust. Like a close friend, familiar cattle have a smaller flight zone and need more pressure to move. Less trust takes less pressure.

The consultant uses a vehicle metaphor. With shoulders as a steering wheel, the rib and hips can be pressure points to apply for directional movements. The body language works like a foot on or off the gas pedal and some shuttle-shifting, slowly pressing and releasing to get a response.

Longtime mentor and animal behaviorist Bud Williams discarded the notion that moving livestock involves luck — at least not when you know what you’re doing.

Disciplined learning Special-forces military teams train to understand what another person is thinking, what they will do in any situation, to predict what will happen so there are no mistakes.

“You can’t bring a new person in and expect them to know, if you haven’t shown them or studied each other,” Lukasiewicz says, suggesting new ranch hands watch and learn before ever stepping into the corral.

“A cow can focus on one or two people at a time,” he says. “It doesn’t take but two people to sort cow-calf pairs.”

The process should be quiet with little movements, but also efficient. Some ranch clients sort 350 pairs in 30-40 minutes, but that only happens with teamwork.

The USDA Meat Animal Research Center (USMARC), with its 8,000-head cow herd and 6,400-head feedyard, is a testament to the benefits of a change in approach. In just six years working with Lukasiewicz, herd demeanor has changed dramatically, says USMARC livestock manager Chad Engle.

Among the 28 cattle breeds with no genetic selection pressure for docility, Engle says he’s seen a difference even in those with bad stigmas. They’ve also incurred fewer accidents and injuries to people, too.

|

“All professional athletes watch film of themselves,” Lukasiewicz says. “And I consider myself a professional athlete at the end of the day.” [Photo by Kip Lukasiewicz] |

“Doctor Kip has evolved my thinking on training new employees,” he says. The need for experience on a résumé has been replaced by “want to” in the interview.

Winning a sporting contest takes discipline, and good stockmanship is no different.

“All professional athletes watch film of themselves,” he says. “And I consider myself a professional athlete at the end of the day.

“You’re watching film on the other team,” he explains, remembering the video of himself when he was learning from behavior consultants Tom Noffsinger and Williams. It takes disciplined study of normal tendencies and finding ways to manipulate them to get what is needed from the animal.

Visuals are still important to Lukasiewicz, whether it’s a drone shot above a facility or just watching cattle load out. How cattle behave as they move though pens or where they place their feet on unlevel ground tells what the animals need.

“By doing that, I designed a chute load-out with steps,” he says. “The width and depth of the steps gave more animal comfort as they were loading or coming off the truck.”

Being in the cattle business comes with high risk and investments.

“So make sure it’s right,” Lukasiewicz says.

The bottom line Science is clear about what does and doesn’t work, which makes “treatment failure” frustrating.

“Vaccines have higher efficacy when cattle aren’t stressed or worked up,” Engle says. Avoiding psychological pressure leads to success at weaning, “and that starts the day a calf is born.”

To get calves settled into the feedyard, they have to eat and drink, he says. If they’re doing those things, the chance of sickness is much lower.

Every year USMARC weans 6,500 calves. Today, it isn’t uncommon to find them up by the bunk chewing their cud and laying in the bedding within 48 hours, hardly a bawl to be heard.

When cattle have positive interactions with people, it’s more fun for everyone.

“I hope cattle enjoy our interaction,” says Byron Ford, cattle feeder near Cairo, Neb. “When you learn to work cattle this way, they look forward to seeing you.”

It makes his role as caregiver easier, too. Prey animals are experts at hiding sickness, so when they’re more comfortable it’s easier to find those having a bad day, Ford says.

The biggest change Ford made was a switching from a tub and sweep to a Bud Box, which allowed a more natural flow through their facility. “And it’s safer for the people moving the stock,” he adds.

“Good health isn’t secured with just a needle and syringe, it’s our approach,” Engle says. “If we treat an animal, something went wrong in the system. Not treating calves or having people get injured is hard to put a price tag on.”

Making big changes requires leader buy-in, and the leader isn’t always atop some corporate ladder.

“Sometimes the team leader isn’t the smartest or most well-equipped,” Lukasiewicz says. “But they are the person that is relatable and inspiring.”

It just takes the action of one person to show others the way.

Editor’s note: Morgan Marley is a producer communications specialist for Certified Angus Beef LLC.