Calm Replacement Females Pay

Low-stress stockmanship pays off when handling replacement heifers.

To have easy-to-handle cows, you need to set the stage with proper handling and training when they are young. Working with heifers is similar to training a young horse; you want their first experiences with people to be good. Do not give them any reason to fear or mistrust people.

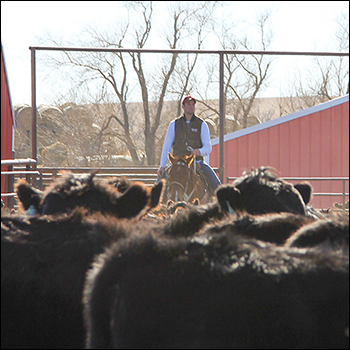

Jon and Breezy Millar of Millar Angus Ranch near Sturgis, S.D., handle their cattle frequently from birth.

“As the calves are born, cows with bull calves go to one pasture, and cows with heifers go to another pasture. We spend a lot of time with them, checking calves, checking pairs. We’re often out there on horseback or on foot, walking through them,” Jon says.

The Millars calve in January and February, and first-calf heifers calve in early January. They calve in the barn. The cows are accustomed to being handled on foot, because that’s how they are handled when processed as weanlings and when they have their first babies.

The ranch started pasture weaning about eight years ago.

“I really like this method because it is low-stress and the calves stay quiet. We just pull the cows out and put them in an adjacent pasture. The heifers have mama right through the fence, so they don’t get all riled up and spooked. This is much easier on them than sorting them off and putting calves in a corral and taking their mothers far away,” says Millar.

“We spend a lot of time walking through them or riding through them after they are weaned. Then we bring them home to their winter pasture. When we feed them during winter, we’ve made a habit of walking through them daily. After you feed, you walk through them, so they associate you with something good. The weaned calves are eager to see us,” Millar says.

|

It starts when they are babies, because they realize their mothers are not afraid of us, so they aren’t either. If the cow doesn’t run off, her baby doesn’t associate you with something scary, says Jon Millar. |

His son and hired man help feed the heifers, and they all understand the program. Millar admits it’s easier and faster to just drive by and drop off feed, but he insists taking the time to walk by those heifers pays off.

“Those calves realize we are good guys. When we process them, we try to do it with minimal stress, using methods advocated by Temple Grandin. Everything is quiet; no one is raising their voice or hitting them with sorting sticks or Hot-Shots®. We never use a Hot-Shot. Low-stress cattle-handling techniques make working cattle more fun, moving them in a natural flow, making them think it’s their idea,” says Millar.

It takes time to develop these heifers to be user-friendly, but it really pays off later when they are calving for the first time, he says. The heifers can walk into the barn, walk quietly into a pen, and are not afraid if assistance is needed.

If their early experiences with people are good ones, it’s easier from then on.

“It starts when they are babies, because they realize their mothers are not afraid of us, so they aren’t either. If the cow doesn’t run off, her baby doesn’t associate you with something scary. If a cow is wild, we get rid of her. We cull hard on disposition because we don’t like problems — and disposition is heritable. Certain bloodlines are more excitable,” says Millar.

Temperament is partly hereditary and partly formed by experiences.

“The way cattle are handled can make a huge difference. You can take a set of calves with the same bloodlines, split them into two groups, handle them differently, and they become totally different cattle. We see this in some of the calves we buy. Each year we buy about 500 calves to feed, and you can tell which ones have been handled right. It really shows in how they react to people,” he says.

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho. Photos courtesy Millar Angus Ranch.