When and How to Check a Cow

An in-tune stockman will recognize the onset of labor.

Knowing when to check a cow that’s not progressing in labor is crucial, and you must be watching her to know how long she’s been in early labor.

Cody Creelman, veterinarian at Fen Vet, Airdrie, Alta., Canada, tells producers they must be familiar with stages of labor to know what should happen with a normal birth. The cow in early labor may be restless or just more alert than usual.

“One clue an old cowboy taught me is to look for the tail kink. The tail usually drops straight down, but when a cow is in early labor the tail is out a little and kinked a bit,” says Creelman.

“Early labor lasts one to four hours, but can last up to 24 hours. Stockmen in tune with their cattle will notice onset of labor. Stage 2 is when the calf enters the cow’s pelvis. She’s had uterine contractions and weak abdominal cramping, but once the calf starts into the pelvis, this stimulates strong abdominal straining. You’ll usually notice the water bag emerging or fluid rushing out as it breaks.”

This stage (active labor) usually lasts between 30 minutes and 2 hours, depending on whether she’s a first-calver, or upset by your moving her into a calving pen or into the barn, which may delay things. Stage 2 ends with expulsion of the calf, and Stage 3 is shedding the placenta. The placenta is usually expelled within 4 hours, but may take up to 24 hours with no cause for concern, he says.

A rule of thumb when monitoring calving is to look for progression every hour. If she’s actively straining for more than 1 hour with no progress, you need to check her, especially if it’s an older cow that usually calves quickly. This is also true if she’s taking more time than usual in early labor — never progressing into active labor.

“On the other hand, if she’s taking her full two hours but you see progress — water bag, then the feet, then the nose — you can give her a little more time. But if you see just the water bag (or the feet), then no more progress, it’s time to check,” he says.

|

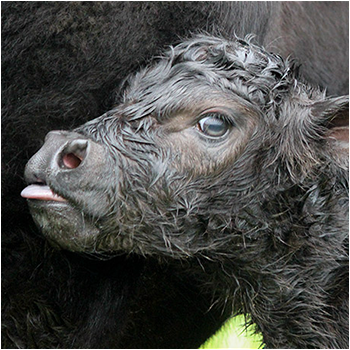

This stage (active labor) usually lasts between 30 minutes and two hours, depending on whether she’s a first-calver, or upset by your moving her into a calving pen or into the barn, which may delay things. Stage 2 ends with expulsion of the calf, and Stage 3 is shedding the placenta. The placenta is usually expelled within four hours, but may take up to 24 hours with no cause for concern, he says. [Photo by Shauna Hermel] |

On a rare occasion you may see the placenta coming out first. That means the calf is detaching and can’t live much longer.

“There are other odd things [to look for], such as the calf coming breech — just its tail in the birth canal — or the calf’s intestines or abnormal hemorrhaging from the cow,” says Creelman.

If you need to manipulate the calf to correct a problem, time yourself. If you’ve attempted to correct it for more than 30 minutes, Creelman says, it’s time to call your veterinarian or load up the cow and take her to town. Being unsuccessful for 30 minutes means something needs be changed in order to still have a live calf.

If nothing enters the birth canal, maybe due to a breech presentation or a uterine torsion (a twist in the cervix that the calf can’t come through), the cow may not begin abdominal straining. You might think she’s still in early labor, but if you wait too long, the placenta detaches and the calf dies.

“The earlier the better for intervention. My best outcomes are when clients checked the cow early and call me early. It never turns out well if someone has been trying for four hours, and now I get the phone call,” he says.

The worst-case scenario is when the cow was restless all day yesterday, but the producer doesn’t call for help until today, he notes.

Sometimes the calf isn’t progressing because it’s too large. You need to determine whether it’s too large to be pulled and needs a C-section.

“One clue is the legs crossing. If it’s a normal presentation (front legs extended with the head between them), if those legs are crossing over each other, it’s usually because shoulders and elbows are too large coming through the pelvis,” he says.

“Anther rule of thumb, when I reach in to assess the situation, is to make sure there’s room over the top of the calf’s head. If you put your hand over the head and can’t get your fingers between the calf’s forehead and the cow’s pelvis, he’s too large to come through,” says Creelman.

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho. Photo courtesy Cody Creelman.