Keep it Quiet

Low-stress handling is affected by facilities, human actions.

The past 25 years have seen improvements in cattle-working facilities and handling philosophies, but some cattle operations still need to “tune up” their handling methods.

Joseph Stookey, a cattle producer and recently retired professor from the Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Saskatoon, Sask., Canada, says there are several good designs for corrals and runways that help cattle flow through better than traditional configurations.

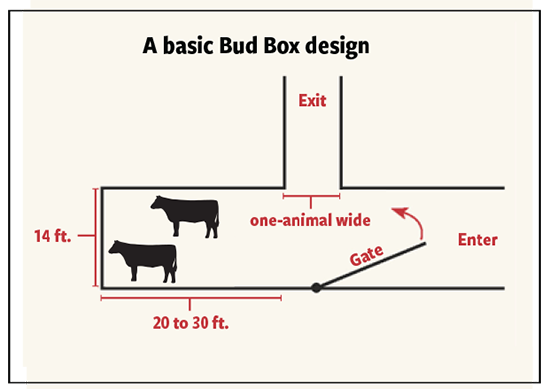

The Bud Box is a short alley in which cattle are moved into a blocked end that is about 20 feet long — depending on how many cattle are typically being worked. |

He notes a few configurations that can work well, but must be set up correctly to work as intended. For example, curved alleys to the squeeze chute work well because cattle don’t see the chute at first and just follow the animal ahead. A Bud Box and a strip gate, where a calf can duck under a panel and into a different pen than its mama, are also good options. The animals should be going back toward the way they came from, and not toward a new direction.

The Bud Box is a short alley in which cattle are moved into a blocked end that is about 20 feet long — depending on how many cattle are typically being worked.

“The gate where they came in is closed behind them and you take a step toward the cattle, from the side where the chute is attached in an L-shape. As the cattle try to move around you to go back out the way they came in, with just a little side pressure you can get them to go right into that chute,” he explains.

Since it’s very close to where they came in, they naturally go into it.

When stripping calves off to a separate pen or pasture, you can use a panel that calves can duck under, but the cows can’t. As the pairs file past, calves tend to hold back, and cows are more apt to go by. You can just step out a little and direct the calf under the panel. The calf will still follow mom, but now it’s got a fence between it and her and it’s in the pen for the calves while the cow goes out of the corral. If there’s room for both of them to keep traveling along together, though separated by a fence, they don’t come back to the sorting gate and are not in the way of the continuing sort.

The key to good cattle handling, however, is not the equipment — it’s the people. A person who handles cattle quietly with minimal stress can easily work cattle in a poor facility. A person who gets cattle agitated and stressed may have trouble working them in a good facility, Stookey says. It’s not difficult to work cattle in any kind of facility if you handle them right. This is especially true with cattle that are accustomed to being worked quietly and calmly, and that respect and trust you.

Cattle — especially nervous, flighty cattle — are easily upset by noise. Both people and chutes can make a lot of noise.

“There are some rubber bumpers that can be installed on parts of the chute that can quiet the noise,” Stookey says. “Metal chutes are noisy, and this in itself can get cattle upset. Noise is never a good thing. If you can make people shut up and only visit during a coffee break or lunch rather than when standing around the headgate, it makes a huge difference.”

Solid-side chutes accentuate sound.

“They act like a megaphone or sound tunnel,” he says. “I worked with a facility at the university that had concrete flooring, and we’d scrape it out after putting cattle through the tub. I’d be out there scraping and hear students on the inside cleaning up and hear everything they said. People don’t realize how well the sound carries through those facilities. When we are all yakking up at the front, we make the job much harder for people loading the chute in the back.”

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho. Photo by Kasey Brown.