How Much Bull Power Do You Need?

Considerations for buying bulls this season.

From how many bulls to turn out to how a bull’s genetic profile will affect herd productivity, Mark Johnson offered commercial cattlemen tips to consider when selecting a new herd sire. The longtime livestock-judging coach and associate professor of animal science at Oklahoma State University shared his comments Jan. 5 during the “Bull Buying Blueprint” educational session hosted by Angus University at the Cattlemen’s Congress in Oklahoma City, Okla.

|

Determining how many bulls to turn out is the first step, said Johnson. “We’re ultimately trying to get those cows serviced and settled and calving as early in the ensuing calving season as possible.”

If calves grow at roughly 2 pounds (lb.) per day, he explained, having cows calve a heat cycle earlier equates to about 40 lb. of extra payweight at weaning.

As a general rule, if they have passed a breeding soundness exam (sometimes referred to as a BSE), yearling bulls that are still growing and maturing can cover about one cow per month of age, Johnson said. Thus, if you plan to turn out a bull at 15 months of age, you can expect him to breed 15 cows within a defined 45- to 90-day breeding season. As bulls grow and reach maturity, they can cover more cows, he continued.

“By the time they get to 2 years of age,” he said, “they’re kind of like professional athletes in the prime of their career. They ought to be good for about 25 to 35 cows for a few years.”

Eventually, as they get to the age of 6, older bulls become more prone to problems. While some bulls can hold up longer — even to age 8-12 — they are higher-risk for getting their job done successfully, Johnson said. “I think everybody’s got to assess that for themselves relative to what kind of risk they want to take.”

How much does a bull cost?

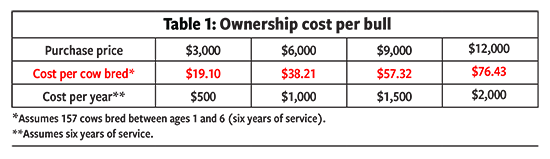

New bulls are an investment. Johnson encouraged cattlemen to break that investment down to the cost per cow exposed and provided the example of a purchase price of $3,000, $6,000, $9,000 or $12,000 (see Table 1). Assuming a bull covered 12 cows as a yearling, 25 as a 2-year-old, and 30 per year through age 6, he’d breed 157 cows in his lifetime, he estimated. By dividing the initial purchase price by the 157 cows serviced, you can calculate the cost per cow serviced.

|

“If you look at those numbers in [red], it looks like a pretty cost-effective thing to invest in a good bull,” said Johnson. “Think about what he’s doing for you in terms of being the full-time employee that checks heat, puts the cow in the chute, does the semen thawing, the artificial insemination (AI) and delivering that to where it needs to be. Even if you’re paying $12,000 a bull, $76 a head over his lifetime in production is pretty cost-effective if we think about the value of genetics and what a good bull can add.”

What can a good bull add?

Which bull will add the most value to your calf crop will be unique to your situation, Johnson pointed out, recognizing the many genetic predictors available to support decision-making. How you use them to your advantage becomes a matter of working through a list of things.

- 1. Analyze your current level of herd performance. “You’re going to have to measure these things,” Johnson said. “It’s tough to improve something if we can’t quantify where we’re at with it at a given point in time.” Some helpful measures include cow weights, calf weights, breeding status, calf weights at weaning and herd health indicators.

- 2. Consider your marketing program. “For all those EPDs (expected progeny differences) and genetic values that we currently have at our disposal, typically, when we market calves is going to dictate that there’s only a handful of them that become really critical to us in our operation and impact our bottom line,” said Johnson.

- 3. Consider whether you will keep replacement heifers. It makes a big difference in where you can focus your selection pressure, Johnson explained. If you are retaining replacement heifers, sire selection will account for the majority of the genetic change in your cow herd over time. If you’re not retaining or marketing replacements, maternal traits are of little value.

“Selection pressure itself is a really precious commodity,” he added. “We don’t want to squander it on traits that don’t actually improve our bottom line or lead to potential profitability.” - 4. Identify your selection goals.

|

Bull buyers can search EPDs with the search function at the top right of angus.org. |

Johnson said bull buyers can realize value from the registrations of their bulls. He recommended doing an animal search on the www.angus.org website (type registration number into the search box in the upper right corner) to get the most current EPDs on the bulls that have contributed genetics to their cow herd. An animal’s EPDs may change over time as more information is added to that animal’s record and pedigree, so it’s good to review the information prior to buying your next bull.

“Whatever bull or bulls in our operation sired that set of cows that are achieving a certain level of herd performance right now can be used to compare to the next set of bulls or bull that we’re interested in using,” Johnson said.

He used an example of a cow-calf operation that at weaning found mature cows averaged 1,400 lb., 85% were pregnant, and their calves averaged 500 lb. With a little math taking into account the percent calf crop weaned, he calculated the pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed to be 410 lb.

“If we look at those 1,400-pound cows weaning off 410 pounds of their weight, they’re actually weaning off a little over 29% of their mature weight. So what does that mean to us?” he asked.

If five bulls were responsible for siring that set of 1,400-lb. cows, we can look up the average of their EPDs and equate that to a current level of performance.

|

Looking at the EPDs of bulls being considered for purchase in relation to the average of those that produced current performance levels, bull buyers can estimate where those new prospects could take them from a performance standpoint. Using the figures in Table 2, Johnson offered a projection of how the “new” bull’s EPD profile would affect herd performance.

- With a mature weight EPD (MW) 20 less than the average of the previous herd sires, Johnson said, we can expect the next generation to weigh, on average, 1,380 lb. at 4 to 7 years of age vs. the current 1,400 lb.

- With a heifer pregnancy (HP) EPD of 15 vs. the previous bull lineup’s average of 9, one could expect heifer pregnancy to move from 85% to 91%.

- “Accordingly, we’re going to see an 88% calf crop weaned,” Johnson calculated.

- Weaning weight (WW) will remain at 500 as the new bull’s EPD matches those of the past.

- Pounds of calf weaned per exposed female would increase by 30 lb. as a result of improved pregnancy rate and percent calf crop weaned.

- The percentage of mature cow weight weaned would increase by about 3% to 32% because you would wean 440 lb. of calf off a 1,380-pound cow.

Any time you consider a bull to purchase or use by AI, first look at your own operation and think about your production system, Johnson concluded. “Think about where you’re at, when you market, how you’re going to use that bull. It’s going to lead you down the path to determine what EPDs are more important to you and what traits you want to improve and what you can expect a generation down the road after you’ve done that.”

Also speaking at the Angus University session were Jeff Mafi, regional manager for the American Angus Association, and Jill Peine, nutritionist with Ridley Block Operations. To listen to all three presentations, access the “Bull Buying Blueprint” webinar at https://www.angus.org/university.

Angus Proud

In this Angus Proud series, Editorial Intern Jessica Wesson provides insights into how producers across the country use Angus genetics in their respective environments.

Angus Proud: Bubba Crosby

Angus Proud: Bubba Crosby

Fall-calving Georgia herd uses quality and co-ops to market calves.

Angus Proud: Jim Moore

Angus Proud: Jim Moore

Arkansas operation retains ownership through feeding and values carcass data.

Angus Proud: Les Shaw

Angus Proud: Les Shaw

South Dakota operation manages winter with preparation and bull selection.

Angus Proud: Jeremy Stevens

Angus Proud: Jeremy Stevens

Nebraska operation is self-sufficient for feedstuffs despite sandy soil.