Five Misconceptions About Liver Flukes Debunked

Knowledge is power against resilient liver flukes.

Parasites in cattle are nothing to mess with. The liver fluke is no exception. Previously an issue with which only producers in the wet regions of the Gulf and Pacific coasts had to deal, these dynamic pests have become a worsening problem for producers across the country.

The economic losses from a liver-fluke infection are challenging to determine, as many cattle don’t show outward symptoms, liver flukes are difficult to detect, and infections aren’t uniform within a herd. Flukes have been found to be a persistent issue. Jody Wade, a veterinarian with Boehringer Ingelheim, is concerned for several reasons:

- Due to the recent migration of liver flukes, producers and veterinarians who haven’t had to deal with them have limited education on how their life cycle affects cattle, as well as how to properly treat and prevent an infection.

- The negative effects — diminished reproductive health, lowered feed efficiency, slowed growth rates and overall diminished productivity — can be costly if left untreated.

There are many challenges surrounding liver flukes, but debunking some major misconceptions will help producers take them on.

Misconception No. 1: They’re just like other parasites

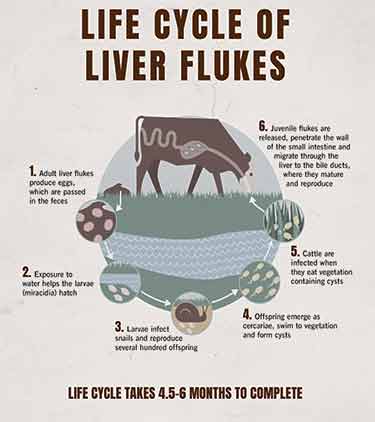

In order to effectively treat and prevent liver-fluke infestation, it’s important to understand their life cycle. It is far more complex than that of a typical parasite.

“Because of liver flukes’ unique life cycle, they have to depend on a specific water pattern to survive, which includes tapping into a Pseudosuccinea columella snail — also known as a Lymnaeid snail — as an intermediate host for a couple months,” says Wade.

The parasite emerges from the snail and attaches to plants in or near water sources where cattle graze. Once cattle ingest liver flukes at their small, developing stage, the flukes start to destroy liver tissues before growing into adults and laying eggs. The eggs then pass through the animal in the manure, where they hatch into larvae that then search for snails, continuing the life cycle.

Misconception No. 2: Flukes are only a regional problem

In the past, liver flukes only showed up in cattle in the moist environments of the Gulf and Pacific coasts. However, more recently, liver flukes have successfully migrated to 26 states. Partly due to the modern movement patterns and transportation of cattle, wildlife and hay, and partly due to shifting rain patterns, liver flukes have become an issue for a whole new set of producers.

Robert Gukich, a veterinarian with Lake Wales Large Animal Services in Florida, says he has seen an uptick of infestations in his area.

“We are used to flukes in Florida, but in the last four or five years, we’ve seen more cattle diagnosed,” he observes. “It could be a result of the mild winters we’ve had and the snails not burrowing as deep into the soil to save themselves, and therefore being more available for flukes.”

With the spread of liver flukes across the country, any producer with wet pastures and snails is going to be susceptible to a potential issue.

“With any amount of rainfall that produces standing water, conditions are prime for a fluke to find a snail and live out its life cycle,” says Wade. “With cattle traveling across the country, liver flukes are likely to travel and make a go of it, no matter where they end up.”

Misconception No. 3: Parasites won’t affect my herd in a drought

During a drought, it might seem liver flukes and other parasites would be less of an issue due to their reliance on a wet environment. However, no matter the weather, cattle are always drawn to water, Gukich explains. “Even in high, dry and sandy areas, we have found flukes in cattle because they are drawn to any sort of water — holding ponds, water troughs, etc. — and they will still make their way through a life cycle involving a snail, even if conditions aren’t ideal.”

Keeping cattle away from extremely wet areas seems a no-brainer to prevent flukes, but cattle will always need water. In the wet seasons, you can try to keep cattle out of the major wetlands, but they will always be drawn to the grasses in wet areas as dry areas are eaten up and wetland grasses tend to have more nutritional value.

Misconception No. 4: An infestation is only apparent post-slaughter

Though post-slaughter discovery of liver flukes is without question the most obvious way to find an issue, it is certainly not the only option.

“In areas regularly dealing with liver flukes, fecal egg count reduction testing (FECRT) is a routine practice,” notes Wade. “Running diagnostics on fecal samples is an easy way to quickly identify an issue under the microscope.”

In Gukich’s region in Florida, he will often test twice if he suspects an issue and the first test comes back negative.

“Because of the different stages of infection in the animal, we may not see eggs passed in a single sample,” he explains.

FECRT is pertinent to discovering an issue and is particularly important in regions with a higher prevalence of liver-fluke issues.

Misconception No. 5: A parasite treatment is a catchall

Though cattle infested with liver flukes rarely show obvious signs, an infestation can cause a slew of negative effects, including reduced conception rates, which may have far greater ramifications. Assuming a traditional dewormer will cover you in a fluke-infested area is a misconception Wade says he wants to correct.

“Stopping liver flukes before they migrate through the bile ducts, usually in the fall, is crucial,” Wade asserts. “Treating cattle with a special compound called clorsulon is your best option to knock them down.”

Finally, Wade emphasizes, “If we can shut down liver flukes, then we can keep cattle on course to perform like they’re supposed to and be productive contributors for a producer in the long run.”

Wade recommends working with a veterinarian to establish a strategic deworming program. How and when you decide to treat for liver flukes will depend on in what region of the country you are located. A veterinarian can help you create a protocol unique to the circumstances of your operation.

Editor’s note: This article is provided by Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA.