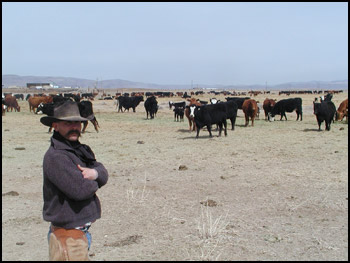

Ron Torell

Back to Basics

Calving heifers: An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Most of our first-calf heifer stories are similar in nature, whether we calve out one heifer or 700. Take, for example, the breached deliveries, the 95-pound (lb.) calves out of "calving ease sires," or the pinched sciatic nerves and paralyzed heifers. There is always the story of the wild heifer that tore up the barn and mucked out the help, the swollen noses and tongues, and the slow-to-get-up and hypothermic calves. And let's not forget the stories of poor mothering ability. Perhaps the most common calving story is the one involving sleep deprivation on the caretaker's part.

In this month's edition of "Back to Basics," let's interview a few Northeastern Nevada owners/managers of large cow-calf operations. They advise an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Let's hear what that ounce of prevention is. In an accompanying story, "Cowboy Midwives: Tips from the Pros," let's interview veteran midwife cowboys who calve out hundreds of heifers per year on these large Nevada cow-calf operations.

Jon Griggs, manager of Maggie Creek Ranches of Elko, Nev., oversees the selection, development and calving of 500 English-bred replacement heifers per year. Griggs says calving problems with first-calf heifers can never be eliminated, but they can be held at bay through proper selection, development and breeding.

"We initially keep 20% more heifers than we need, applying selection pressure at three separate times: weaning, development and breeding," he explains. "We feel identifying and eliminating problem heifers up front is the way to go. Factors such as poor doers, disposition, fertility, pelvic area, these are all reasons for us to send her down the road prior to breeding."

Dan Gralian, manager of TS Ranches of Battle Mountain, Nev., agrees with Griggs relative to selection pressure up front and feels the next crucial element in reducing calving difficulties in first-calf heifers is proper development.

Tim Draper of the TS Ranch in Battle Mountain, Nev., oversees the calving of more than 700 first-calf heifers each year. He subscribes to the philosophy "an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure."

"The TS Ranch develops approximately 700 replacement heifers each year," he says. "I know that many ranchers now prescribe to the new trend of low-cost heifer development, but we are very fortunate to have the feed source and facility to develop our replacement heifers to 65% to 70% of mature weight [by breeding]. This gives us a 1,000-pound (lb.) heifer at calving. We believe that a properly developed heifer will breed up early, have less calving difficulty, breed back quickly and stay in the herd longer. We consider heifer development a sound investment in our cow herd production."

He goes on to say, "Another prime factor in reducing calving difficulty is good heifer-bull selection. We look for low-birth-weight bulls that still have acceptable growth and maternal traits. Many of our future replacements are out of first-calf heifers."

Ed, Mike and Paul Sarman, owners/managers of Lee Livestock of Lamoille, Nev., subscribe to all the above and suggest incorporating synchronization and artificial insemination (AI) to high-accuracy calving-ease sires to the list.

Pictured are the new hires on the TS Ranch. These bulls went to work in spring 2009, so their offspring will be delivering as you read this article. Dan Gralian, manager of TS Ranch of Battle Mountain, Nev., searches hard to find quality calving-ease bulls.

"Using high-accuracy calving-ease-direct (CED) AI sires does not eliminate problems, but it sure minimizes them," state the Sarman brothers. "We breed our heifers to calve one heat cycle prior to our mature cows and only leave quality calving-ease cleanup bulls in for 35 days. This allows us to concentrate our efforts on calving heifers for a short period of time, and then we can turn our attention to the mature cows and other spring work."

Griggs agrees with the Sarman brothers and relates his experiences with natural breeding vs. utilizing high-accuracy AI calving-ease-direct bulls.

"Before we initiated an AI program, we were assisting 25% of our heifers at calving time. For the past 10 years, utilizing high-accuracy AI calving-ease sires, our assistance rate has held steady at 8%. When you are calving 500 heifers in a 45-day period, you do not have time to wipe the nose off every calf. Utilizing these high-accuracy bulls allows us to get the job done with less labor," Griggs concludes.

Matt McKinney, manager of Bently AgroDynamics livestock operations in Garnerville, Nev., agrees with Griggs and the Sarmans relative to AI breeding of heifers. McKinney also recognizes the importance of maintaining a tight calving interval of 45 days or less. McKinney subscribes to the "bred-right, fed-right" theory.

"It all comes down to a sound genetic package that is handled and developed properly, bred to a calving-ease sire (preferably a high-accuracy AI sire), and calving in a short calving interval. To clinch the deal, heifers need to be fed an adequate pre- and postpartum ration. Following this recipe has decreased our assistance rate to 5%. It makes life a lot easier at calving time," McKinney concludes.

There is a misconception that if you synchronize and AI heifers during a five-day period that all these calves will be born in a five-day period 283 days later. The feeling is that you will be overwhelmed at calving time. This is not the case, says Alan Sharp of Ruby Valley, Nev. "Generally we get a 65% to 70% conception rate to first-service synchronized AI. Most if not all of these high-accuracy calving-ease sires are short-gestation bulls that start calving 16 days before their due date. Calving continues up to their textbook 283 gestation due date. Our AI calves are spread out over a 12- to 16-day interval. This allows us to concentrate our labor during this time period and get it over with," Sharp concludes.

John Jackson of the Petan Ranch, which is located in northern Elko County, Nev., favors calving at 3 years of age unassisted in the brush.

"We have the ability to keep these heifers "bull free" for the first two years of life. This allows us to slowly develop heifers to reach target breeding weight over a two-year period. We can do this much cheaper on standing winter and summer range forage. Allowing that extra year to grow and mature reproductively, we feel we make better range cows. We used to lose a lot of cows on the second or third conceptions. That is not the case now for our second and third conception fallout has decreased. Our weaning percentage actually increased with 3-year-old calving. Life sure is simpler this way."

As always, if you would like to discuss this article or simply would like to talk cows, do not hesitate to contact me at 775-738-1721 or torellr@unce.unr.edu.

Comment on this article.

[Click here to go to the top of the page.]