Problems Underfoot

Wet conditions often lead to hoof problems.

Fall rain that leaves pastures and pens boggy can present challenges for hoof health in cattle. If feet are continually wet, the hoof horn and skin become softer and more easily damaged, which can lead to foot rot, punctures, abscesses and other serious conditions.

Foot rot is a common problem, says Jan Shearer, Iowa State University professor and extension veterinarian. “This infection affects the skin and soft tissues of the foot. This makes it unique because most other foot conditions, with exception of digital dermatitis, are within the hoof itself.”

The treatment is antibiotic therapy, and the sooner it's administered the better, Shearer says. “Foot rot is very responsive to systemic antibiotic therapy if given early, but in many cow-calf systems, we may not see the animal soon enough.”

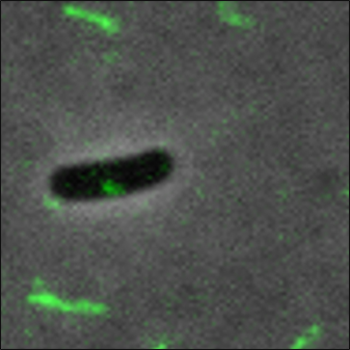

|

Foot rot is characterized by swelling, pain (severe lameness) and an interdigital lesion — between the claws. The claws are usually spread apart by this swelling. [Photo by Heather Smith Thomas] |

Shearer notes that by the time it is discovered, it may be a complicated problem, especially if the infection goes deeper into the tissues and infects the joint.

When there is simply a soft-tissue infection, it creates a cellulitis and can involve a significant amount of the foot, up to the fetlock and higher, creating swelling. Foot rot is characterized by swelling, pain (severe lameness) and an interdigital lesion — between the claws. The claws are usually spread apart by this swelling.

Swelling is a classic sign of foot rot, but many people may see the lameness from a distance and assume it is foot rot. The swelling and lameness may be due to a broken bone, abscess, nail puncture, snakebite, or something jammed up into the interdigital skin and tissues between the claws.

Before treating the animal, make sure the lameness is due to foot rot, Shearer advises. “The biggest problem I see regarding foot problems is that nearly every animal that develops lameness is treated with a systemic antibiotic, whether the foot is swollen or not. A person may treat a lame cow or bull two or three times with antibiotics, only to discover that this treatment won’t resolve the condition. On closer inspection, the problem is actually a hoof disorder such as white line disease, sole ulcer or other traumatic lesion to the sole.”

Failure to treat these conditions may lead to more serious problems, he warns. Improper treatment of hoof lesions can result in infections that go deep into the foot, requiring surgical correction or euthanasia in the worst-case scenario.

“Many times I’ve seen well-meaning people treat animals two or three times; then when they don’t respond, bring them into the clinic for a more thorough examination. By that time the lesion may be complicated, leaving the veterinarian with few options except surgery,” Shearer says. “This is sad for the animal, because if it had been treated properly and sooner, it would have had a chance to make a full recovery. Once these lesions become complicated, treatment with an antibiotic is a waste of time and money, with possibility that the problem will become worse and unfixable because the infection has gone too deeply into the foot.”

Swelling is not the only sign of foot rot; to be sure it’s foot rot, you need to see a lesion between the claws.

“If you don’t find that, you need to carefully look at the weight-bearing surface of each of the claws to see if there is some other problem,” Shearer explains. “True foot rot will have generalized swelling on both sides of the foot, up to the fetlock or higher, and a foul-smelling necrotic interdigital lesion.”

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a freelance writer and cattlewoman from Salmon, Idaho.