Mineral Imbalances Should Be Considered In Cattle Deaths

Texas A&M AgriLife offers expertise, assistance in livestock mineral toxicity, testing.

Ranchers need to keep in mind that the wrong quantities of minerals can be dangerous or even deadly to cattle, say experts from the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service.

When it comes to cattle and minerals, what works for a rancher 700 miles away may actually work better for you than what works for a neighbor 7 miles down the road; it all depends on what is in your soil, supplements, feed, forage and water supply.

“There is no one-size-fits-all approach to minerals,” stresses Joe Paschal, AgriLife Extension livestock specialist, Corpus Christi. “What works for your neighbor’s cattle won’t necessarily work for you. There are a lot of factors producers must take into consideration.”

“Proper livestock nutrition is a key factor in your cattle’s health and productivity,” adds Thomas Hairgrove, AgriLife Extension cattle veterinary specialist in the Texas A&M University Department of Animal Science. “Knowledge of your herd’s mineral status is fundamental to developing an optimal herd health program.”

What works for one livestock operation will not always work for a neighbor when it comes to mineral supplements. Your state extension service can help test for your herd’s needs. [Photo by Texas A&M AgriLife] |

The key to understanding individual needs centers on the total nutrition of the herd. For example, diets high in protein and/or potassium (K) or low-carbohydrate diets can impair magnesium (Mg) absorption, says Hairgrove.

He says zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu) need to be absorbed in a specific ratio. Excess zinc reduces the amount of copper absorbed and excess iron (Fe) or sulfur (S) can interfere with absorption of other minerals.

“In other words, an excess or deficiency of one mineral affects how other minerals function in the animal,” says Hairgrove.

Sometimes, he says, extreme cases can lead to death in a herd. So, what happens when you find a dead cow, or multiple dead cows, over a period of a few months or a year? Hairgrove and Paschal hope producers and veterinarians realize AgriLife Extension offers an invaluable resource.

Burleson County case

“In Burleson County we had a producer who had almost 20 head of cattle die over a period of a year,” says John Grange, AgriLife Extension agent for Burleson County. “This was an older producer in his 90s and when his son became aware of the situation, they consulted their local veterinarian.”

The veterinarian was having trouble diagnosing the issue, so she contacted Texas A&M AgriLife. Grange said once he, Paschal and Hairgrove put their heads together, they decided to conduct several tests to rule out possible causes.

“Working as a team, we conducted tests on hay, forage, soil and water samples,” he says. “Dr. Hairgrove also pulled blood and urine samples on the cattle. This case showed the importance of how strong the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service is and how, together, we were able to help our producer.”

Grange says they were able to rule out many common issues and get to the core problem for the producer. By using the entire team they were able to help this producer, and ultimately aid in another local case.

Testing

The Burleson County producer found most of the animals observed experienced a sudden death in the pasture. The few animals observed appeared to exhibit signs of grass tetany, which are usually associated with magnesium deficiency.

Urine and blood samples were taken from 10 cows and submitted to the Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory to determine mineral status. These indicated only a low serum copper status, which would not cause sudden death. Magnesium deficiency cannot always be evaluated from urine or blood.

The most sensitive and practical test to determine the animal’s magnesium status and predict supplementation value requires measuring urinary creatinine and magnesium. Further testing indicated these cattle were deficient in magnesium in their diet. These cows were determined to also be deficient in selenium, as shown in alternate testing strategies.

Analysis of soil, forage and water confirmed the deficient dietary status of this herd. Protein, energy and mineral supplementation based on forage, water and soil analysis began. Follow up with the owner indicates no more death loss.

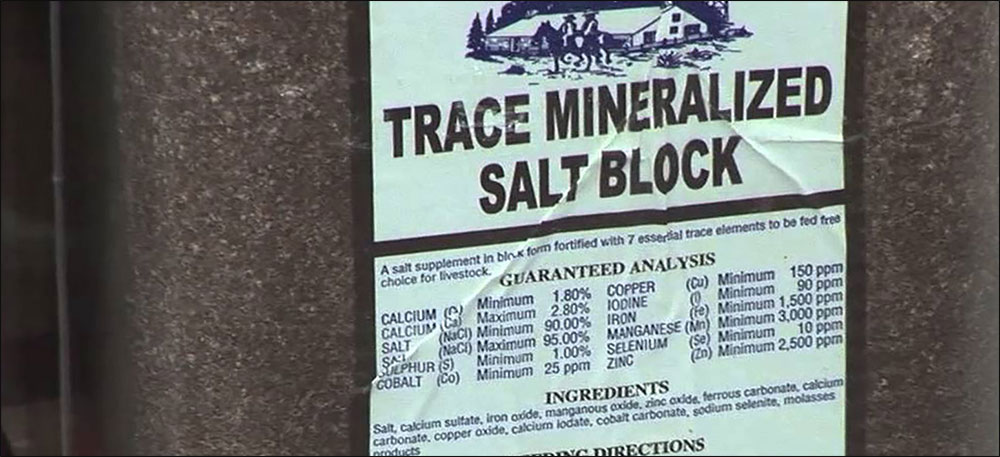

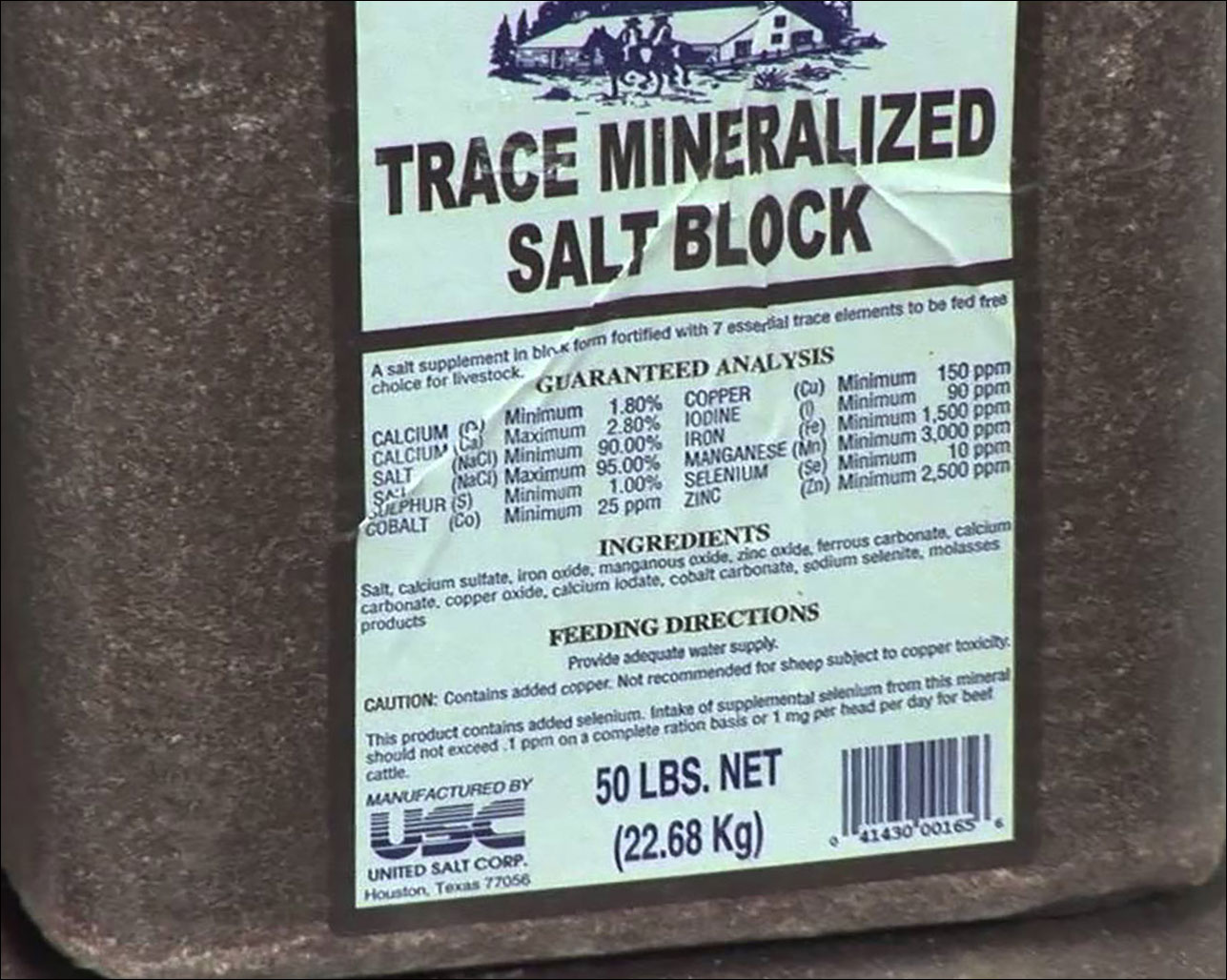

“It is never as simple as putting out a mineral block and assuming that it will meet your cattle’s needs,” stresses Hairgrove. “This producer’s mineral supplementation consisted of white salt, yellow salt and trace mineral block, yet the deaths of 20 animals appear related to their mineral status.”

Hairgrove says the take-home message is to work with your local veterinarian and extension educators to interpret laboratory results relative to your cattle’s body condition, forage and water quality, and potential for disease or toxic plants.

Upshur County case

Hairgrove and Paschal both recall other memorable cases during the past year scattered across the state. A novel case involves bison in Upshur County.

“When the producers first came in my office about their dying bison, I didn’t have a clue about bison,” says Kaitlyn Slover, AgriLife Extension agent for Upshur County. “I quickly called my regional program leader, Larry Pierce, and he pointed me in the direction of Dr. Hairgrove.”

Bison are known to have issues with internal parasites, especially with high-density stocking. After speaking with Hairgrove, Slover determined she needed to collect fecal samples to determine if internal parasitism was the cause of the deaths. Internal parasites were present, but the results of three necropsies indicated a severe mineral imbalance with high zinc and low copper liver levels.

“We also ran soil samples, water samples, forage samples and hay samples,” she says. “Through all these tests, we were able to confirm the bison were suffering from high zinc and low copper levels.”

They also consulted with Jason Banta, AgriLife Extension beef cattle specialist in Overton, on feed, minerals and hay. They were ultimately able to come up with a plan for the producers.

“Trying to find research on bison was our biggest struggle; that’s why the applied research we have started will be so vital to the industry as a whole,” says Slover.

“Everyone hates to hear about animals dying, but the research that we have been able to conduct because of these deaths will prove to be important for other producers worldwide for years to come,” Slover says.

Anderson County case

In Anderson County, a producer lost four cows during about a year. This was concerning because the cattle were not old and didn’t have any apparent health issues. The producer contacted the local AgriLife Extension office to help in determining the possible causes.

“Within Texas A&M AgriLife we are lucky to have good resources to help with situations like this,” says Truman Lamb, AgriLife Extension agent for Anderson County, who pulled together a team to help solve his stakeholder’s problem.

Joining Lamb were an AgriLife Extension veterinarian, an AgriLife Extension beef cattle nutritionist and private veterinarians. After looking at and ruling out a range of possibilities and evaluating tissues samples, it was determined that the cattle most likely died of copper toxicity.

“Unfortunately, trace mineral toxicity is becoming more common, especially when producers feed multiple supplements with added trace minerals or use drenches or injectable mineral products in addition to a well-formulated mineral supplement,” said Lamb. “It is important to provide a mineral supplement, but you don’t want to overdo it, as that can lead to additional problems.”

Texas A&M AgriLife resources

“The reality is there is a lot of cropland that has been turned into pasture that is very low in soil mineral — not just nitrogen, phosphorus or potassium, but many of other soil minerals, too,” says Paschal. “Before putting animals out to graze on a new location, a little soil and water testing and forage analysis can go a long way. If you know what you are working with in advance, it will really be to your animals’ benefit.”

Taking tissue samples from cattle is one of the ways to test the overall health of a herd and to determine any mineral deficiencies they may have. [Texas A&M AgriLife photo courtesy Joe Paschal] |

Between AgriLife Extension, Texas A&M AgriLife, Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory and the rest of the extensive Texas A&M network, nearly any question a stakeholder has can be answered, and any test that needs to be run can be done.

“We want producers to be aware that no matter where in Texas they live, there’s an AgriLife Extension county agent they can call for help,” says Grange. “We encourage ranchers to call us first when they have a problem, not last. Even if we do not know the answer, the access and resources available to us are extensive, and we will know how to find the AgriLife expert who can provide the answer.”

Paschal added that “Dr. Google” doesn’t have the answers and should not be considered a reliable source. A little testing, common sense, and best management practices can go a long way in stopping preventable deaths.

Editor’s note: Susan Himes is a communications specialist for Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service and Texas A&M AgriLife Research based in San Angelo.