Advanced Tech With Real-world Applications

New tech opportunities have been tried and tested.

The Range Beef Cow Symposium, hosted Nov. 16-17, in Rapid City, S.D., gathered several technology companies and university extension specialists to give practical demonstrations on new technologies. Read more to find out how ranchers have been able to apply them.

Virtual fencing

You’ve likely heard of shock collars and invisible fences to prevent dogs from going beyond a boundary in their yard. Well, that exact same concept is being used as “virtual fencing” for cattle.

“Virtual fencing allows for greater control over animal movement on the landscape,” said Krista Ehlert, assistant professor and Extension range specialist with South Dakota State University.

With 1 mile of traditional barbed fence costing $8,000-$10,000 or more, virtual fencing offers a significant opportunity to reduce capital and labor costs, and ultimately improve grazing management, Ehlert explained.

Currently, three companies have made virtual fencing products available commercially. These include e-Shepherd, an Australian-developed product now owned by the fencing company Gallagher; Nofence, which was developed by a Norwegian ag-tech startup; and Vence, which was the most recently developed product by a San Diego startup in 2016.

Ehlert said all three products operate using similar technology. The animal wears a weighted collar with a small battery and audio pack, as well as two electrodes on the back of the collar. Once wearing the collar, if the animal comes within a set distance of the virtual fence boundary, an audio cue will begin to emit from the collar to the animal. If the animal does not turn around from the audio cue, but continues forward toward the virtual boundary, a shock will be sent through the two electrodes.

Ehlert said animals typically learn quickly to turn around and move back from the virtual boundary in order to avoid the audio cue or shock. She suggested applications of virtual fencing technology include protecting an area with young trees from being grazed, excluding riparian areas or dugouts with bad water from being grazed, or creating grazing zones within a larger pasture to successfully rotationally graze the pasture — all without having the cost and labor to install physical fence.

Currently, the cost for virtual fence technology from Vence includes $35 to rent a collar for one year, plus $10 for the battery. A collar can be moved to different animals within the rental period. Additionally, a $12,500 base station tower is needed to emit the virtual fence boundary signal that corresponds with the collars. The range for a tower is about 10 km (approximately a 6-mile radius), and the towers are portable. Vence recommends at least two towers for most operations.

HerdDogg offers animal traceability with ear tag

A room of hopeful ranchers listened intently as George Owen described an ear tag that could help them monitor and track their cattle in real time from an app on their smartphone. Owen is the beef and bison program manager for a Wyoming start-up company called HerdDogg.

The company’s “DoggTags” are named for the data generator gatherer — or Dogg — technology that they utilize. Readability can be gathered from up to 100 yards from the reader for 250 tags. A first iteration of the tags only had a 30-yard reader capability.

The tags, which can be applied with a standard tag applicator, are powered by Bluetooth® and transmit data to the company’s HerdDogg Cloud Platform, where a producer can access the real-time location information on a smartphone or computer.

One producer in the audience noted that he envisioned using HerdDogg to put a reader close to a gate — or a watering source. He stated, “Then you know which animals are coming and going.”

Another suggested if pulling cattle off of forested lands or large pasture, having the tags and reader could help indicate how many are missing, and if the reader could pick up locations, possibly pinpoint where missing animals were.

Currently, HerdDogg offers two types of ear tags: the TraceTag costs $10 per tag and can last up to five years. It can be read from as far as 100 yards and is a straight replacement for radio frequency identification (RFID); while the WelfareTag costs $15 per tag, and can last up to two years. It has the same features as the TraceTag, but also comes with enhanced health monitoring to detect estrous cycles.

Ultimately, the company’s aim is for the HerdDogg tag to offer animal traceability through the entire food supply chain — following the animal from one buyer to another and eventually providing information to the consumer. With permission from the producer or branded-beef company, a consumer could potentially scan a code on the final meat package that shares information about when and where it originated, breed information, where it was processed, etc.

Owen concluded, “There is huge potential with this technology.”

The producers in the room seemed to agree.

Learn more at herddogg.com.

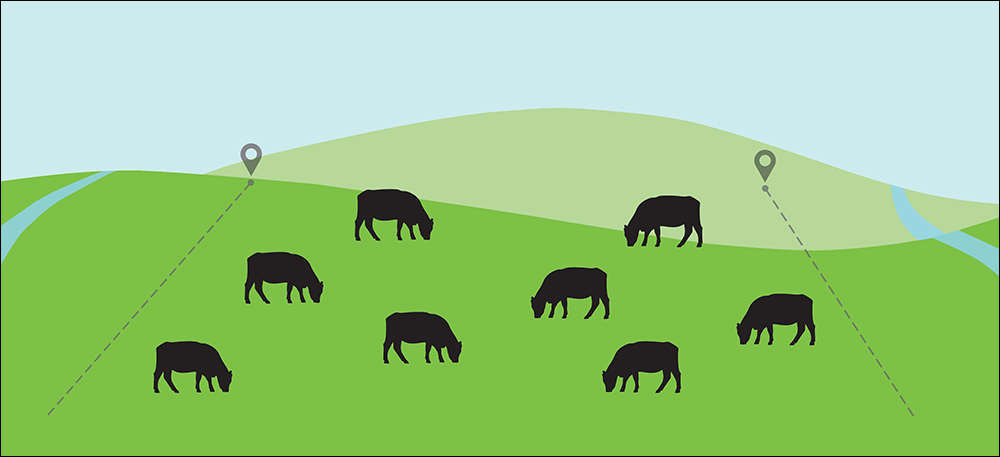

Using GPS technology to track livestock behavior

Having a global positioning system (GPS) collar to track the location of each animal on your farm or ranch once sounded like science fiction, but today the technology is reality.

GPS trackers have been used for a few decades in the research realm, both for livestock and wildlife, but often each individual tracker cost $1,500-$2,000. Today, the cost of some GPS tracking collars retrofitted for livestock can be in the $50-$60 range, making this technology more attainable for research and ranch applications, according to range scientists Jamie Brennan with South Dakota State University and Mitch Stephenson with the University of Nebraska.

Brennan and Stephenson explained that GPS devices store animal location at timed intervals, which allows for building a map showing their movements over the course of a day, a week, a month, etc. Previous research has used these livestock location data points and paired them with landscape mapping software.

As examples, GPS technology has been used to study livestock grazing patterns within patch burned areas, to analyze the influence of landscape topography and/or forage quality on grazing patterns, as well as to evaluate how placement of supplement feed blocks affects livestock distribution in a pasture. Additional research has also used GPS tracking devices to monitor relationships (based on location) between individual cows within a herd and to study the possible influence of livestock genetics on grazing behavior, including the distance cattle may travel from water and differences in average elevation use.

Now, as GPS tracking devices are becoming less expensive and allow tracking in real-time, ranchers have the ability to track some of these metrics within their own cow herd in the future, noted Brennan.

Stephenson pointed out that just as precision technology increased efficiency within cropping systems, GPS trackers offer similar potential for management and production efficiency in livestock.

These researchers suggest benefits include checking animals remotely and knowing if an animal is outside the pasture or traveled away from the herd. Additionally, they offer an opportunity to monitor health and track if an animal hasn’t come to water or is not moving.

For producers looking at GPS trackers, Brennan noted that the technology is advancing quickly and advises evaluating the battery life, ruggedness of the collars, and the software and data analytics that are compatible with the device.

Ceres and mOOvement are two companies mentioned that are currently developing GPS ear tags for livestock.

Editor’s note: Kindra Gordon is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Whitewood, S.D. We want to give you more of what you want. Let us know what that is! Please follow this link to take our biennial reader survey: https://bit.ly/ABBreadership22e.

Angus Proud

In this Angus Proud series, Editorial Intern Jessica Wesson provides insights into how producers across the country use Angus genetics in their respective environments.

Angus Proud: Scott Sproul

Angus Proud: Scott Sproul

Oklahoma operation learned wisdom of moving calving season to better suit their marketing needs.

Angus Proud: Bubba Crosby

Angus Proud: Bubba Crosby

Fall-calving Georgia herd uses quality and co-ops to market calves.

Angus Proud: Jim Moore

Angus Proud: Jim Moore

Arkansas operation retains ownership through feeding and values carcass data.

Angus Proud: Les Shaw

Angus Proud: Les Shaw

South Dakota operation manages winter with preparation and bull selection.

Angus Proud: Jeremy Stevens

Angus Proud: Jeremy Stevens

Nebraska operation is self-sufficient for feedstuffs despite sandy soil.