The Brown Stomach Worm: A $2 Billion Problem

Learn how to identify and control the most economically important parasite in today’s cattle herds.

Ostertagia ostertagi is the most common and economically important parasite in cattle. Also known as the brown stomach worm, it is estimated to cost the U.S. cattle industry $2 billion per year due to lost productivity and increased operating expenses.

“On beef and dairy operations, we’re not seeing the traditional signs of worms, such as skinny animals with rough hair coats, anymore,” says Stephen Foulke, Boehringer Ingelheim veterinarian. “Instead, internal parasite infections manifest as poor productivity, including reduced feed intakes, slower growth rates, delayed breeding, decreased milk production and depressed immune responses.”

Studies show that a brown stomach worm infection can reduce weight gain by up to 20 pounds (lb.). Milk production can see a decrease between 2 lb. and 5 lb. per day.

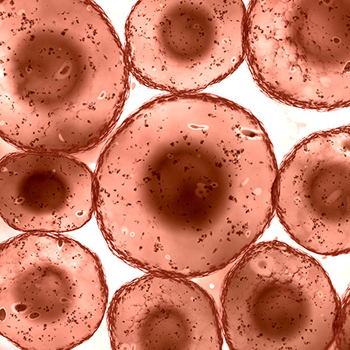

How do herds become infected? Unlike other stomach worms, the brown stomach worm has the unique ability to penetrate the lining of the abomasum and become dormant, so it can survive during weather that’s too cold or too hot. When conditions improve, the larvae can emerge all at once, causing severe inflammation and irritation, reduced feed intake and sometimes even death.

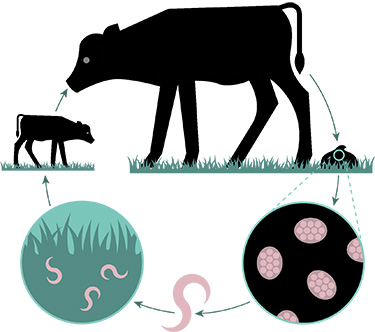

Foulke breaks down the basic life cycle below (illustrated in Fig. 1):

- Adult parasites lay eggs in the gastrointestinal tract of cattle.

- Eggs are expelled from the cattle through feces.

- Eggs hatch and develop into infected larvae.

- The infected larvae crawl onto the grass that cattle graze on.

- Larvae are ingested by cattle.

| Fig. 1 Basic brown stomach worm life cycle |

|

Stocking density and weather conditions can influence the likelihood of this cycle continuing, and consequently the number of parasites present at any given time.

“Parasites place themselves in the best position to be ingested by cattle,” explains Foulke. “They try to stay at the top of the grass blades during the day, and migrate back down to ground level overnight.”

Studies have found that the climate at the base of the grass is very favorable for larval survival and can harbor large numbers of parasite larvae. Some larvae migrated as far as 15 centimeters (cm) down into the soil and were able to return to the surface for ingestion.

Rainfall and other adverse weather conditions allow larvae to be more easily transported away from the fecal matter. In fact, a minimal amount of water can transport larvae up to 35 inches away from their original location.

To best protect your herd from parasites, Foulke encourages producers to look for a weatherproof dewormer. A local veterinarian can help you determine the parasite load in your animals and on your pasture throughout the year, as well as adapt control methods to manage parasites in all weather conditions.

Managing the brown stomach worm “Producers often ask about the best deworming protocol, but unfortunately, that answer is different for every farm,” says Foulke. “The way you’re going to deworm a dairy herd in the Northeast is going to be very different than deworming a stocker operation in Florida.”

To minimize the effect these parasites can have on herd performance and profitability, Foulke advises both beef and dairy producers to work with their veterinarian to perform routine fecal tests on their cattle, and implement management protocols accordingly.

Editor’s note: This article is from Boehringer Ingelheim. Fig. 1 adapted from file from broadhead. Photo by Kasey Brown.