Oddball Tick Causes ‘Foothill Abortion’ — Now There’s a Vaccine

After decades of research, ranchers have a convenient management tool.

The cause of cattle abortions in foothill regions of coastal and central California, southern Oregon and Nevada, and parts of Arizona baffled ranchers and veterinarians for many years. The unique pathogen that causes death of the fetus is transmitted by the bite of a soft-bodied tick, Ornithodoros coriaceus, that inhabits these regions.

Jeffrey Stott, professor of pathology, microbiology and immunology at the University of California-Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, says that by the 1940s researchers realized this disease was different from brucellosis.

“The California legislature provided funds for the veterinary school in Davis to identify the pathogen. It took a long time, but we figured it out,” he says.

The tick that transmits this disease lives in arid regions and burrows into the ground where deer or cattle bed. If the ticks haven’t taken a blood meal for a month or more, they crawl out of the ground, locate an animal lying there, and attach for about 30 minutes to engorge with blood. Unlike hard-bodied ticks that stay on the host a long time, these ticks drop off quickly and burrow back into the ground.

|

Cows abort about three to five months after being bitten by a soft-bodied tick called Ornithodoros coriaceous. |

“They can survive two to three years without a blood meal, and live for 12 to 20 years. The tick was identified as the vector in the 1980s, but it took another 20 years to identify the oddball bacteria, recently named Pajaroellobacter abortibovis, causing abortion. It is difficult to culture because it only replicates once every few days, whereas most bacteria multiply very rapidly,” he says.

Cows abort about three to five months after being bitten by the tick. Some ranchers reduced incidence of abortions by changing the breeding season, using tick-infested pastures after cows are past six months of pregnancy, or exposing yearling heifers to tick-infested pastures before breeding to develop immunity before they were bred.

“We began developing and testing an experimental vaccine 10 years ago, collaborating with the University of Nevada at Reno, using their confined beef herd. Those cattle are naïve and never see foothill abortion. The vaccine proved to be close to 100% efficacious in that situation,” Stott says.

The USDA approved expanded trials — collaboration between the California Cattleman’s Association (CCA) and the veterinary school. The CCA signed ranchers up to be part of the trials.

“The ranchers had to keep records and provide us with data. We vaccinated 10,000 to 12,000 cattle per year,” says Stott.

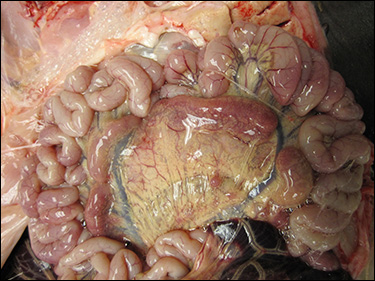

|

The mesenteric lymph nodes are enlarged in aborted calves due to the tick bite. |

Prior to a pharmaceutical company receiving a conditional license, all vaccinations had to be approved by the USDA. There was a lot of paperwork, but once they received the conditional license (September 2020) the company started distributing it in California, Nevada, Oregon and Arizona.

The vaccine is live and frozen, and it must be transported in liquid nitrogen.

“There is a long list of do’s and don’ts in handling this vaccine; but, if done properly, it works well. It must be administered by a veterinarian or under supervision of a veterinarian. Many producers have their veterinarian do it the same time they give Bang’s vaccination. People need to be cautious with this vaccine. If the person giving the vaccine is pregnant or even thinking about being pregnant, it would be wise to steer clear of it,” says Stott.

The vaccine is expensive, but losing calves is even more expensive. It’s a big cost up front — about $25 to $30 a dose.

“With a typical vaccine, you’d probably be giving a booster the first year and another booster every year after that. You only need to vaccinate heifers once, and it lasts at least three years — and you have more live calves all those years,” clarifies Stott. “It more than pays for itself in one year.”

Vaccinated cattle have immunity for about three years.

“Sometime after that, you might need to give a booster if there is minimal tick activity to create continual exposure and sustaining immunity. For resident animals in areas with foothill abortion, this will be a heifer vaccine and largely protect the herd because those animals will be immune as they work into the herd,” he says.

Producers in other areas are also interested in the vaccine because it opens more markets for their animals. Females could be vaccinated before being shipped to tick-infested areas.

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a freelance writer and cattlewoman from Salmon, Idaho. Photos courtesy Jeffery Stott.