Three Ways to Take Action Against Lepto hardjo-bovis

If reproductive efficiencies seem to be slipping in your herd, the underlying cause may be the result of leptospirosis.

From early embryonic deaths to lower pregnancy rates, stillbirths, abortions and even weakened calves, Lepto hardjo-bovis affects all stages of beef cattle reproduction. With minimal clinical signs along with these reproductive inefficiencies, the presence of leptospirosis can quickly affect herd profitability.

“The financial impact of leptospirosis can be huge, especially in cow-calf operations,” said Jody Wade, veterinarian with Boehringer Ingelheim. “If cows aren’t able to produce a healthy calf every year, it’s going to cost producers a lot of money down the line.”

Leptospira outbreaks are most common in spring and summer, and the bacteria can survive in the environment for months. A recent study conducted in six states representing a cross-section of climates and management practices found that Lepto hardjo-bovis was prevalent in 42% of U.S. cattle herds, and was more likely to be found in warmer, wetter climates.1

With the unusual weather patterns many cattle producers have been facing this year, implementing Lepto hardjo-bovis prevention strategies will be key in protecting reproductive efficiency and maintaining a profitable operation down the road. To help ensure reproductive success in your beef herd this summer, Wade recommends the following management practices.

|

It can be difficult to prevent cattle from drinking infected water, especially if producers are unaware leptospirosis is present in their herd,” explained Jody Wade. “Maintaining a fresh water source for cows to drink from will help decrease the likelihood of them ingesting Lepto hardjo-bovis bacteria.” |

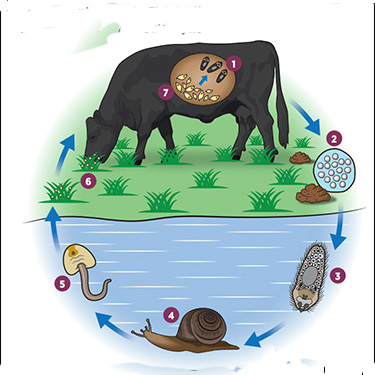

1. Minimize standing water Unfortunately, Lepto hardjo-bovis is most commonly spread via urinary shedding, making it easily transmittable. Water tanks, pastures, ponds and streams that infected cattle have access to can all be contaminated with Leptospira. If cattle are drinking the water containing leptospirosis pathogens and have not built up prior immunity to the disease, they will likely be infected.

In fact, odds of the disease developing are nearly two times greater in operations where ponds and stock tanks are used as the main water source, since the pathogen can survive for extended periods in stagnant water.1

To prevent the transmission of Lepto hardjo-bovis, Wade suggests draining or fencing off low-lying or swampy areas so that cattle do not have access to standing water. He also encourages producers to clean water tanks routinely, as they can hold leptospirosis bacteria for a long time.

“It can be difficult to prevent cattle from drinking infected water, especially if producers are unaware leptospirosis is present in their herd,” explained Wade. “Maintaining a fresh water source for cows to drink from will help decrease the likelihood of them ingesting Lepto hardjo-bovis bacteria.”

2. Practice strict sanitation Control of rodents, feral swine populations and canine hosts is strongly encouraged, as wild animals can serve as maintenance hosts and expose cattle to the bacteria. Keeping pens clean and isolating aborting cows for treatment will also help to prevent the spread of leptospirosis.

3. Vaccinate cattle prior to breeding While urinary shedding is the most common way for leptospirosis to spread, the infection can also be passed through reproductive fluids, uterine discharges, infected placenta, milk and semen.

“Because there are so many ways cattle can be exposed to Lepto hardjo-bovis, the most effective preventive strategy is to implement a complete reproductive vaccination program,” stressed Wade.

To increase the likelihood of successful pregnancies, Wade recommends vaccinating cattle with a combination vaccine that is labeled to prevent urinary shedding of Lepto hardjo-bovis. Vaccinations are especially important for heifers, as their lifetime production hinges on a successful first pregnancy.

“Treatment for leptospirosis is available, but producers will spend a lot of money and time trying to eliminate the infection after it’s already been established in their herd,” Wade concluded. “Vaccinating 20 to 30 days prior to breeding will allow enough time for cattle to develop a strong immune response to Leptospira, and will help protect all stages of reproduction before it’s too late.”

Each operation is unique, so producers are advised to work with their local veterinarian to establish practical reproductive protocols and management practices for their herds.

Editor’s note: This article is from Broadhead on behalf of Boehringer Ingelheim.

1Wikse SE, Rogers GM, et al. Herd prevalence and risk factors of Leptospira infection in beef cow/calf operations in the United States. Bov Pract 2007;41(1):15–23.