In The Cattle Markets

Seasonality in fed-cattle transactions and the role of negotiated cash.

Alternative marketing arrangements (AMA) have once again taken center stage in the cattle market during the last several weeks. It is common knowledge that the use of AMAs varies by geographical region, with Southern Plains feedlots using a larger share relative to Northern Plains feedlots. A long-standing issue is whether each geographical region is contributing a perceived appropriate amount of negotiated cash trade to aid in price discovery. This issue has intensified as the national level of negotiated cattle continues to decline. Lower cash prices and increased volatility due to COVID-19 government quarantine measures and the Holcomb Fire have appeared to intensify this issue among market participants.

In response to historically low cash prices, some industry organizations petitioned the government for further transparency and regulation in the feedlot-packer interface. The first proposed government legislation was the “50-14” rule led by Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Senator Jon Tester (D-Mont.), which sought to mandate large-scale packers to procure a minimum of 50% of all cattle purchased via negotiated cash for harvest in 14 days. There was strong industry response against mandating a level of negotiated cash trade, especially at 50%.

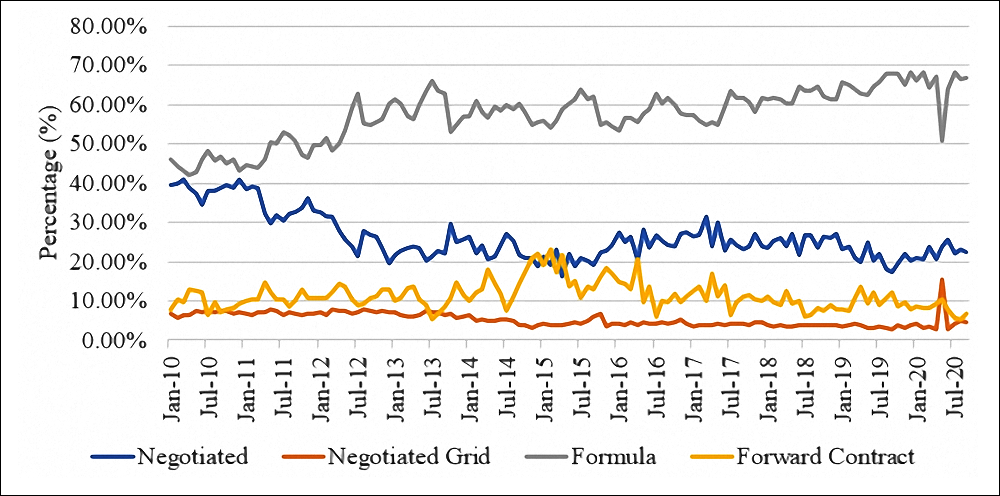

Fig. 2: Historical percentage of live all-cattle transactions, 2010-2020 |

|

Click here for larger image |

The second, and most recent, was a bill introduced by Senator Deb Fischer (R-Neb.) that would authorize USDA to establish regional mandatory minimum thresholds of negotiated cash trades by geographical region with industry comment. It would also authorize USDA to set up a contract library like the one currently available in the hog market. Both bills aim to increase the amount of regional cash negotiated trade, which, in turn, would increase negotiated cash prices received by producers.

However, the supply of fed cattle and demand for wholesale beef determine the price of fed cattle. To increase negotiated fed-cattle prices, both proposed bills would either need to reduce the supply of fed cattle or increase the demand for wholesale beef. These rules would increase negotiated cash transactions, helping in price discovery in each week, but are unlikely to affect the underlying fed-cattle market supply-and-demand condition to increase the local cash price.

If these laws had been in place prior to either the Holcomb Fire or COVID-19, it is unlikely they would have changed packing plants’ ability to process cattle (supply from feedlots) or foodservices’ demand for beef.

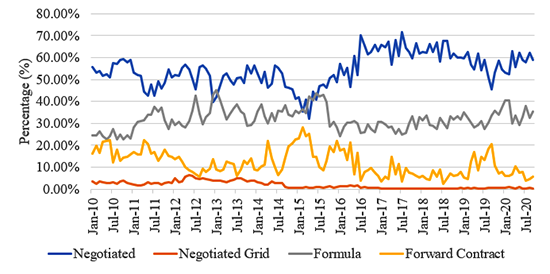

Fig. 3: Historical percentage of dressed all-cattle transactions, 2010-2020 |

|

Click here for larger image |

Currently, national cattle-on-feed numbers suggest the backlog resulting from government quarantines and COVID-19 cases in packing plants has been almost completely worked through.

There have been two primary ways the industry has reacted to these bills. First, the industry tried to increase the amount of negotiated cattle in the market using the proposed “Bid-the-Grid” program. This led to an unprecedented amount of negotiated grid cattle being sold, most notably in Kansas. For example, historically the share of weekly cattle being sold via negotiated grid, either live or dressed, is 5%. In one week, the negotiated grid spiked to 20%, a level not seen in 10+ years. Since then, it has returned to historical levels.

The second reaction has been to develop and advocate for a voluntary framework. This framework would work to have each geographical region increase the share of negotiated cattle if certain levels or “triggers” were reached. This is the industry’s preferred method prior to government legislation.

The ability for voluntary market participation is likely already in the market. Producers choose to engage in AMAs largely because there are market incentives to do so. To get feeders to move away from AMAs toward negotiated cash, the market incentives to do so must be at least as large as those currently offered under AMAs.

For example, during the Holcomb fire, Nebraska producers, who historically sell a large amount of negotiated cattle, switched to more formula/grid sales. One explanation for this is that producers did not believe their cattle quality was being valued in the market. One way to try and (re)capture this additional perceived value was to sell cattle on formula/grid. After the Holcomb Fire, cattle sold via formula/grid returned to historical levels.

One issue potentially confounding understanding the role of negotiated trade is that often cattle sold by transaction (i.e., negotiated cash, forward contract, formula and negotiated grid) report a combined live and dressed trade (see Fig. 1). More cattle are sold via negotiated cash on a live basis. From 2016-2020 approximately 60% of all cattle sold on a live basis were negotiated cash (see Fig. 2). Compare this to the 10% sold dressed via negotiated cash (see Fig. 3). The share of dressed cattle in the overall monthly cattle trade between 2010 and 2019 is about 70%. Thus, if the trend continues toward selling more cattle dressed, then the relative share of negotiated cash will likely continue to decline.

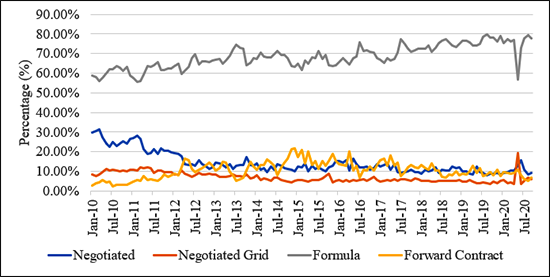

Fig. 4: Seasonality in the percentage of negotiated sales (live + dressed) as a percent of all cattle transactions |

|

Click here for larger image |

So what has been happening to the share of cattle transactions (i.e., negotiated cash, forward contract, formula and negotiated grid) sold on a live basis during COVID-19? In short, there has been little change in negotiated cash as a share of all cattle transactions on average nationally since Jan. 1, 2020. Although there appear to be some regional differences, with Northern Plains states experiencing slightly more volatility in the share of negotiated trade compared to Southern Plains states.

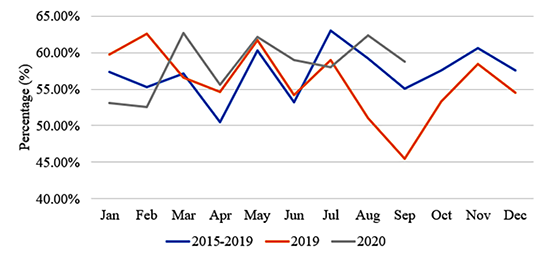

Like most price series, cattle transactions are seasonal. Fig. 4 displays the seasonality of negotiated cash (live + dressed) as a share of all cattle transactions nationally for 2015-2019, 2019, and 2020. There has been no change to the seasonality patterns of negotiated cash trade in 2020 compared to the five-year average. The decline in the third and fourth quarter of 2019 came in large part from the Texas-Oklahoma-New Mexico region not reporting sales because confidentiality requirements were not met. The drop in negotiated cash trade began to fall prior to the Holcomb Fire incident in August 2019. Thus, it is unlikely that the Holcomb Fire caused the lack of reporting, but it could have prolonged it.

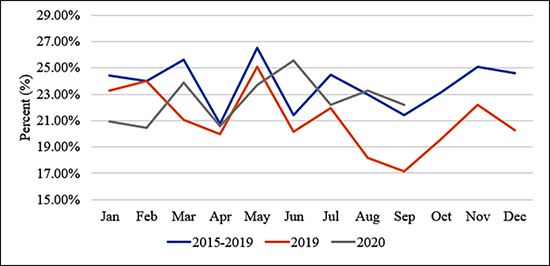

Fig. 5 shows the seasonality of negotiated cash as a percentage of all live-cattle transactions. Year-to-date in 2020, more cattle have been sold live via negotiated cash compared to the five-year average. Even during the government quarantine and packing plant closures (March-August), on average, the percentage of cattle sold live via negotiated cash was above the five-year average. Figs. 4 and 5 show some graphical evidence that the Holcomb Fire and COVID-19 market disruptions are unlikely to have affected the national percentage of cattle sold (live, dressed or live+dressed) via negotiated cash.

Fig. 5: Seasonality in the percentage of negotiated sales sold on a live weight basis |

|

Click here for larger image |

Both proposed bills put forth by the U.S. Senate have stated the need for more price discovery due to the Holcomb Fire and COVID-19 market disruptions. Figs. 1-5 graphically show that the national level of negotiated cash was likely not significantly affected by either market disruption. The current concern surrounding AMAs (i.e., formula/grid pricing) has more to do with lower cash prices received by producers due to market reactions to major market disruptions than AMA’s role in thinly traded markets.

While both bills would bring increased negotiated cash price discovery and transparency in the feedlot-packer market interface, neither are likely to increase the cash price received by producers since they do not fundamentally change the supply of fed cattle, nor the demand for wholesale beef.

Further, it is unlikely that if these bills were implemented prior to either the Holcomb Fire or COVID-19 it would have prevented the backlog in cattle or affected the demand for wholesale beef. If implemented, these policies would create additional transparency, but they would potentially create increased costs and reduce profitability for the entire beef complex. Consistent with the economic theory of derived demand, the additional costs of these policies are likely to predominately be carried by the cow-calf industry.

Editor’s note: This article is adapted and reprinted with permission from the Livestock Marketing Information Center available online at lmic.info. Elliott Dennis is assistant professor and livestock extension economist in the Department of Agricultural Economics at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.