Efficacy vs. Safety

Get the most out of your vaccine protocol with these tips.

Combination vaccines are generally utilized to protect cattle against bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR). Currently there are several inactivated (killed) and modified-live virus (MLV) vaccines for this purpose.

Chris Chase, professor in the Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences at South Dakota State University, says that when vaccinating naïve, open animals or heifers to go into the breeding herd, it’s best to use MLV vaccines because the MLV vaccine mimics the actual infection and produces better immunity. When the goal is to have antibodies in colostrum, however, killed vaccines are better when vaccinating pregnant cows — not only for safety, but also because the killed vaccines contain more antigen. They do a better job of stimulating production of antibodies for colostrum.

“When MLV vaccines first came out in the 1970s and early 1980s, there were safety issues. They were not modified enough and caused some problems, so people started using the inactivated (killed) vaccines. Then the manufacturers began to perfect the MLV vaccines, and it became clear that MLV vaccines had an advantage in turning on the immune response,” says Chase.

Through the 1990s and into the early 2000s, most of the killed vaccines didn’t have very good adjuvants and quality of the antigens was not as good.

“Then the vaccine companies figured out how to improve antigen quality and have also come up with much better adjuvant systems, and they are more effective,” he says.

Chase recommends using inactivated vaccines in pregnant animals, rather than the MLV vaccines, since the latter do present a safety risk. If the animal, for some reason, doesn’t have good pre-existing immunity and viremia develops after the vaccination, it is a problem, he says. The only safe time — and most effective — to use an MLV is on animals that aren’t pregnant and well ahead of breeding.

“There is a safety claim for MLV viral vaccines for pregnant animals, but these studies were done under optimal conditions. Those animals are well-vaccinated; they’ve been on a good vaccination program and good nutritional plane. Every animal that was used in those studies was verified that they were vaccinated earlier — before they were vaccinated during pregnancy. Under these conditions, I think the MLV vaccines are safe,” says Chase.

The label claim for use in pregnant animals, explains Chase, has changed from “safe to use in pregnant animals vaccinated within 12 months with the same product,” to “Fetal health risks associated with vaccination of pregnant animals with modified-live vaccines cannot be unequivocally determined by clinical trials conducted for licensure. Management strategies based on vaccination of pregnant animals with modified-live vaccines should be discussed with a veterinarian.”

No vaccine can be expected to have 100% efficacy under all conditions, he admits.

Under field conditions, not all animals mount the same immune response to vaccination, and some don’t respond at all. Those animals may not be safe to vaccinate with MLV vaccines, even if you’ve followed label directions and vaccinated all animals the same. If for some reason a few animals have less immunity, they may be at risk if you give an MLV vaccine during pregnancy.

The reason labeling the MLV vaccines for use in pregnant cows came about was because ranchers wanted to vaccinate calves prior to weaning to protect them from respiratory disease during stress of weaning.

“Back in 1980, we were doing this all the time — vaccinating calves while they were on the cow, because they were under the least amount of stress,” he says.

This enabled them to mount stronger immune response and gave them protection later when they were stressed during weaning.

“People were vaccinating calves while those calves were still nursing their mothers, and if cows were bred this meant they were nursing pregnant cows. This was the label claim the vaccine companies wanted — a vaccine approved for calves nursing pregnant cows, but the trial USDA came up with to make sure the pregnant cow would be safe, was to vaccinate not just her calf, but also the cow herself,” Chase says.

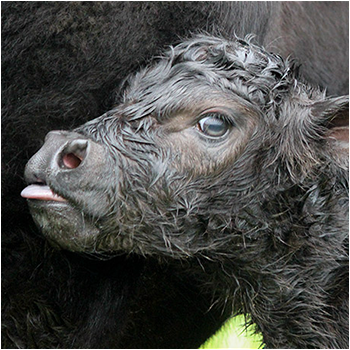

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho. Photo by Shauna Hermel.