Frostbite: Not Just a Risk for Newborns

Extreme weather affects the health of older calves, too.

Calves born in cold weather may quickly become hypothermic if they are not immediately dried off and placed in a sheltered environment, but older calves may also suffer frostbite if they don’t have shelter in a winter storm or during severely cold temperatures. Sick calves are especially at risk.

Steve Hendrick, veterinarian at Coaldale Veterinary Clinic, Coaldale, Alta., Canada, says that if a calf is compromised in any way, such as sick with scours, that calf has a harder time keeping warm. Dehydrated calves are the most vulnerable. Calves with scours can readily freeze ears, tails and feet just because they have poor circulation. The body is trying to keep the important organs alive, concentrating the reduced blood supply around the body core — sacrificing blood circulation to the extremities. Thus the calf’s legs and feet, ears and tail get cold.

“It’s not always the newborns that suffer frostbite. Occasionally an older calf loses his ears or tail — or even his feet if he had impaired blood circulation during cold weather,” Hendrick explains.

Producers who calve a bit later than January-February can still run into problems with late winter storms. The weather may not stay bitterly cold for as long at a time, but a cold, wet snow can severely chill new calves, or even older calves — especially if they are sick.

A calf with pneumonia or scours, outdoors in bad weather, is at high risk for hypothermia.

“The only difference with some of these later storms is that the temperature might not be quite as cold, but being wet and cold can take a toll on older calves as well as newborns,” says Hendrick.

If the calf is cold and miserable, he doesn’t feel like nursing, especially if he’s sick. This becomes a vicious cycle, because a calf that’s off feed doesn’t have the energy to create body heat. Wind makes cold weather many times worse, especially for a calf, because his small body chills much faster than a larger animal. Windbreaks are crucial in any pasture where there are cows with young calves.

No perfect time to calve Producers who calve later to avoid bad winter weather can run into the opposite extreme with hot weather.

“Newborns and young calves are also very vulnerable to heat stress and dehydration,” says Hendrick.

A young calf in hot weather needs a lot of fluid, and if the calf is so hot he doesn’t feel like nursing, he can dehydrate very quickly. A sick, dehydrated calf will also suffer heat stress more quickly than a healthy calf.

Calving in early summer can also create challenges if cows are being bred during the heat of August, when heat stress can hinder fertility in cows and bulls. No matter what time of year you pick for calving, there can be some disadvantages. A producer must try to select a calving season that might work best in their own situation and have a plan in place to deal with possible problems, he advises. You might have some really great weather for a number of years and think it’s a perfect time to calve, and then get hit with unusual weather that can take its toll — unless you are prepared to deal with it.

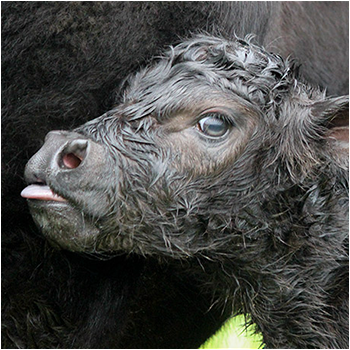

Editor’s note: Heather Smith Thomas is a cattlewoman and freelance writer from Salmon, Idaho. Photo by Jacob Coon, NJAA/Angus Journal Photography Contest.