Get Them Warm

Rewarming methods offered for severely cold-stressed newborn calves.

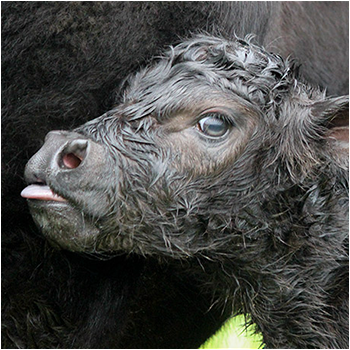

Early spring-calving cow herds have to deal with extreme cold and snow, as we saw last month. Some newborn calves are certain to be cold-stressed after arrival. Getting those cold-stressed calves back to normal body temperatures as soon as possible will save the lives of some calves and increase the vigor of others.

Several years ago, an Oklahoma rancher called to tell of the success he had noticed in using a warm-water bath to revive newborn calves that had been severely cold-stressed. A quick check of the scientific data on that subject bears out his observation.

Canadian animal scientists compared methods of reviving hypothermic or cold-stressed baby calves. Heat production and rectal temperature were measured in 19 newborn calves during hypothermia (cold stress) and recovery when four different means of assistance were provided. Hypothermia of 86° Fahrenheit rectal temperature was induced by immersion in cold water. Calves were rewarmed in a 68° to 77° F air environment where thermal assistance was provided by added thermal insulation or by supplemental heat from infrared lamps. Other calves were rewarmed by immersion in warm water (100° F), with or without a 40-cc drench of 20% ethanol in water. Normal rectal temperatures for baby calves without cold stress should be about 103° F.

The time required to regain normal body temperature from a rectal temperature of 86° F was longer for calves with added insulation and those exposed to heat lamps than for the calves in the warm water and warm water plus ethanol treatments (90 minutes and 92 minutes vs. 59 minutes and 63 minutes, respectively). During recovery, the calves rewarmed with the added insulation and heat lamps used up more body energy metabolically than the calves rewarmed in warm water.

This represents energy that is lost from the calf’s body that cannot be utilized for other important biological processes. Total heat production (energy lost) during recovery was nearly twice as great for the calves with added insulation or exposed to the heat lamps than for calves in warm water and in warm water plus an oral drench of ethanol, respectively. By immersion of hypothermic calves in warm (100° F) water, normal body temperature was regained most rapidly and with minimal metabolic effort. No advantage was evident from oral administration of ethanol. (Source: Robinson and Young. Univ. of Alberta. J. Anim. Sci., 1988.)

When immersing these baby calves, do not forget to support the head above the water to avoid drowning the calf that you are trying to save. Also, it is important to dry the hair coat before the calf is returned to cold winter air. If the calf does not nurse the cow within the first few hours of life (six hours or fewer), tube feeding of a colostrum replacer will be necessary to allow the calf to achieve passive immunity by consuming the immunoglobulins in the colostrum replacer.

Not every calf born in cold weather needs the warm-water bath. Most will survive if moved to an enclosed barn or calving shed with adequate bedding or insulation such as heavy blankets. Be careful if heat lamps are used, and be certain that straw bedding cannot be set on fire. The warm-water bath described above is apparently a method that can save a few severely stressed calves that would be less likely to survive or be weakened if more conventional rewarming methods are used. With 2021 input costs, saving every calf is important to the bottom line.

Editor’s note: This article is reprinted with permission from the Feb. 15 Cow-Calf Corner, a newsletter published by the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, for which Glenn Selk is an emeritus extension animal scientist.