How Much is Too Much?

Use these calculations to figure what you can afford to pay for cow replacements in 2023.

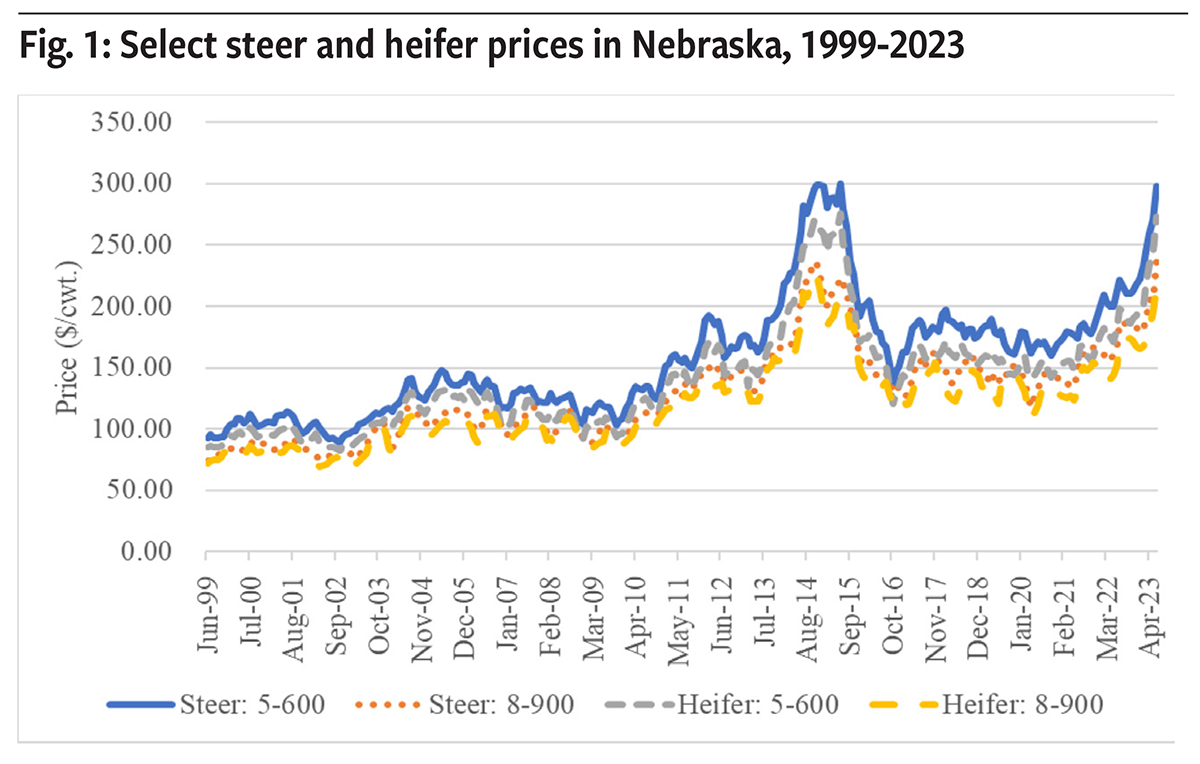

Cattle prices are up. There’s no doubt about that. Nebraska feeder-cattle prices, for example, have risen significantly during the last four months. Nominally, prices are at or higher than where we were in the 2013-2015 cycle. June 2023 average monthly prices for 500-600-lb. steers were approximately $300 per hundredweight (cwt.). The November Feeder Cattle contract at the CME stumbled down through June as the corn market rallied, but it has since recovered and broken previous price resistance levels into $252 per cwt.

As summer begins to come to an end, producers will soon start to make decisions about early weaning and cow culling/retention. Producers looking to buy cows in 2023 need to know how much is too much to pay.

How much should you pay for a heifer this fall?

The answer: It depends. Typical, answer from an economist, right?

So, what does it depend on?

It requires producers to establish some expectations about current and future market conditions. These market conditions generally include animal productivity, calf prices, inflation, cow inventories, weather events, etc., all of which contribute to the value of a replacement cow. Ultimately, these factors combine to produce a single breakeven value, but for simplicity, let’s take each factor separately to see how movement in either direction affects the value we are willing to pay for a cow today.

- Productive life: Each cow has a useful, or productive, life. Some are long, and some are short. The longer she lives, the more value she has. This productive life has a direct tie to the cull rates of the whole herd. While cull rates vary by year and age of cows, they may be used as a rough measure of average cow life. If a rancher has an average annual cull rate of 16%, on average, a cow lasts 6.25 years in that herd (100 ÷ 16 = 6.25).

- Cow productivity: This is separate from the productive life of a cow and is typically measured in terms of the weaning weight of calves. The size and number of calves weaned and sold per cow exposed to a bull will alter this value considerably. Heavier weaning weights imply more income generated per cow. Thus, one can pay more for replacements.

- Cow costs: If weaning weights were all that mattered, we would raise extremely large cows. But, large cows tend to cost more and have larger maintenance costs. What it costs (what it truly costs) to manage a cow affects the value. The higher the cost, the less one can afford to pay for replacements.

- Salvage value: If the expected salvage or cull value is expected to increase over time, what one can afford to pay increases. In the past, these values have been fairly low; however, during the past few years, they have been much higher.

- Calf prices: If cattle prices during the productive life of the cow are expected to be high (or higher) on average, then what one can pay for replacements increases. Understanding the cattle cycle dynamics here is important.

- Interest rates: Higher feeder-cattle interest rates imply more expensive borrowing costs and, thus, less one can pay for replacements. During the past 15 years, interest rates have been declining; however, in the last six months, they have jumped significantly — from about 5.5% to 8.2%. If you are not borrowing money, you can pay a lot more for replacements.

Click here for larger image. |

Click here for larger image. |

What tools can I use to calculate this value?

Gathering, compiling, formatting and estimating all these factors into one estimate is cumbersome. Thankfully, there are several free and accessible tools available. The two I highlight are the 2023 Heifer Replacement Values [University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL)] and 2023 Heifer Replacement Values (file will download on your system) [Kansas State University (KSU)]. The primary difference between these tools is the assumptions/data used in the calculations and how flexible one wants to be in modifying the assumptions.

The UNL estimates are based on the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri (FAPRI-MU) projections for cattle value, as well as the cost of production and related data from UNL’s Gudmundsen Sandhills Laboratory. They are calculated based on a simulation model. Alternative scenarios are provided, but one cannot adjust the model’s underlying assumptions. KSU estimates are largely based on USDA-ERS 10-year projections, are static (i.e., produce one value rather than a distribution of values), and the user can modify most assumptions.

A word of caution: Most tools use a representative operation that does not reflect an individual producer, but rather an average of many producers. There is no expectation that the cost and production assumptions reflect exactly a particular producer. Forecasts, such as the two tools mentioned, are intended to help individuals create a reference point for individual situations and expectations of future events. Producers can use these, other information and their own ideas to arrive at what a reasonable value might be for a heifer/cow purchased or retained for replacement.

Click here for larger image. |

Click here for larger image. |

Example calculations

Total net return from calves is simply the total revenue from calf sales minus the total cost of producing those calves. Net revenue per calf is the total net revenue from calves, divided by the number of calves over the productive life of that cow. For example, $100,000 of total costs divided by 100 calves equals a cost of $1,000 per head (hd.). For every cow that weaned a calf, it cost $1,000. If the average calf weighs 550 pounds (lb.) and brings $2.50 per lb., the expected revenue from calves is $1,375 per hd. (2.50 x 550). The difference is $375 per hd. net return (1,375 - 1,000).

Assume we have an average herd culling rate of 16%. Thus, on average, a cow lasts 6.25 years in that herd (100 ÷ 16 = 6.25). If these conditions are what is expected for the next 6.25 years, then the net return per cow that weaned a calf would be $375. During the life of a newly purchased or raised cow replacement for this herd, it is estimated the average cow replacement will have a net return of approximately $2,344 per hd. (i.e., $375 x 6.25 years). These calculations assume no borrowed money (i.e., interest rate = 0%). This represents the most we should be willing to pay for that replacement.

Change the assumptions

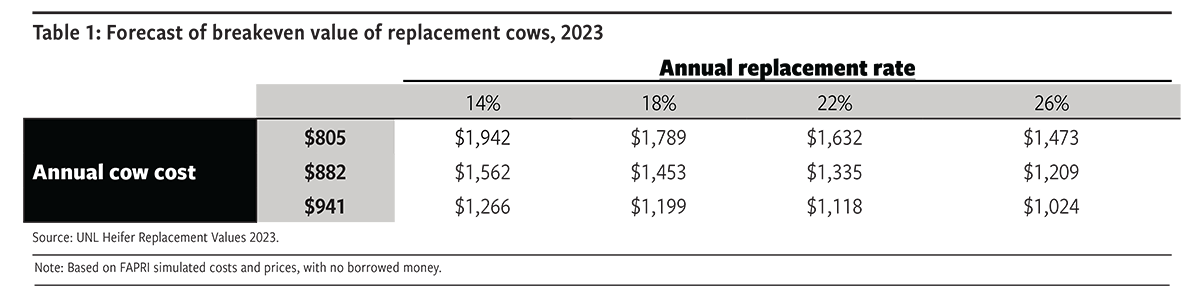

I am sure some are saying they wean at higher weights with lower cull rates and lower annual cow costs. That’s great! What happens if annual cow costs go up and cull rates increase? How does this affect the value of the cow replacement? Table 1 shows a few scenarios with different replacement rates and cow costs using the UNL Heifer Replacement Calculator. This is meant to show how the underlying assumptions affect the value one can pay for cows.

Drought conditions on the mind

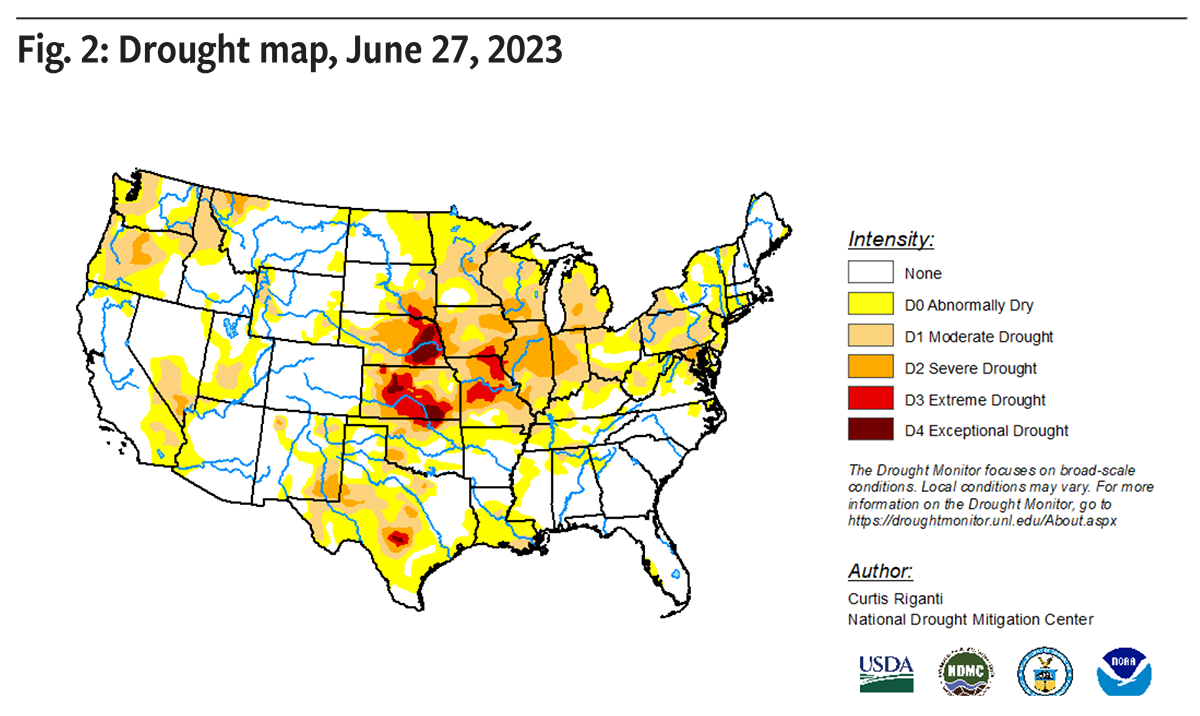

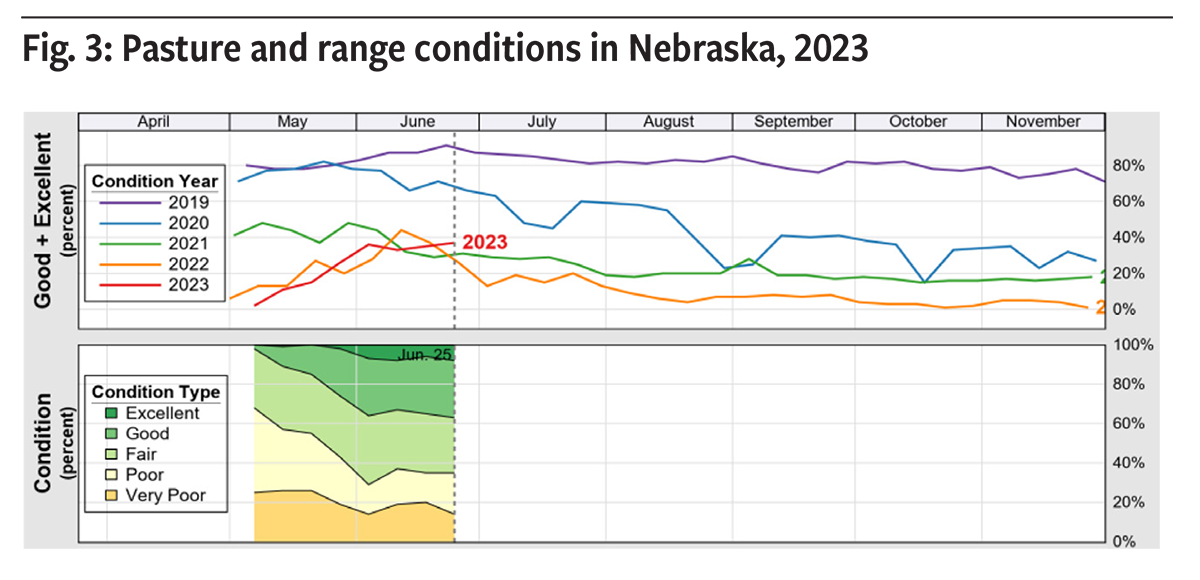

Pasture conditions have been on many producers’ minds this summer in the Midwest, particularly in Nebraska and Kansas (see Fig. 2 — Drought Map). Lack of rain has hampered pasture conditions (see Fig. 3), but more recent rains have provided some relief, allowing both corn and hay fields to improve considerably. The concern is that decreasing pasture and higher feed costs would continue to cause cow liquidation.

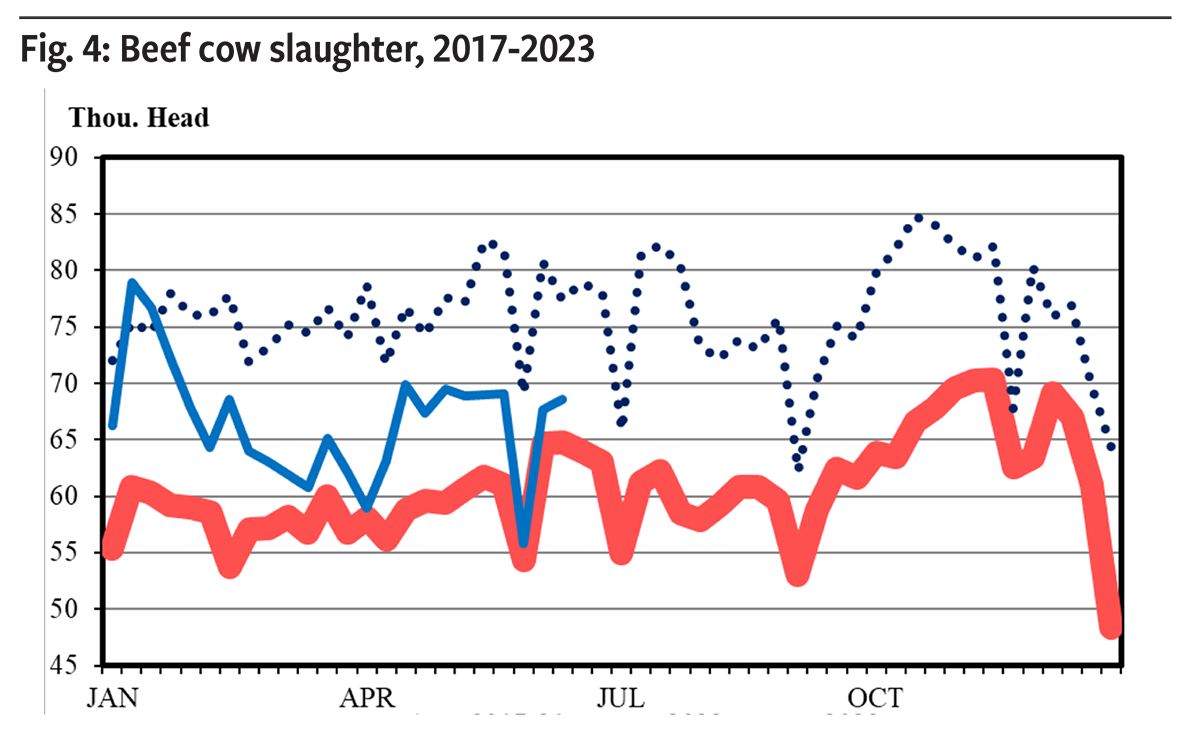

Putting that into our example of “what can I pay for a replacement cow?” indicates that if cow harvest continues due to drought, it could continue to pull up calf prices. Thus, we could pay more for a replacement cow. However, it could also increase costs to raise cows in drought-affected areas. Beef cow slaughter has regulated over highs in 2022 toward the five-year average even though drought has continued in some areas (see Fig. 4). So, the likelihood of drought affecting future cull rates and cow replacement costs appears low.

Editor’s note: Elliott Dennis is an assistant professor and Extension livestock economist in the Department of Agricultural Economics at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. This is an “In the Cattle Markets” article from the Livestock Marketing Information Council.